UDL Tip of the Month 2024

UDL Principle 3: Multiple Means of Action and Expression

The previous two months' teaching tips from CITL’s Universal Design for Learning (UDL) team focused on the first two principles of UDL: Providing Multiple Means of Engagement and Providing Multiple Means of Representation. This month’s tip rounds out our overview of the UDL framework by looking at its third pillar: Providing Multiple Means of Action and Expression.

The principle of Providing Multiple Means of Action and Expression recognizes that students vary in the ways they learn and demonstrate their understanding. Addressing this principle from a design perspective involves creating more inclusive learning opportunities by giving learners multiple ways of constructing knowledge and expressing what they learn.

3 Ways of Providing Multiple Means of Action and Expression

- Multimodal Content: Provide a multisensory learning experience by combining different types of content. This might include text, video, podcasts, graphics, as well as opportunities for engagement like interactive simulations and timelines, embedded self-check questions, and practice options with feedback. This multimodal approach appeals to diverse learning preferences and helps reinforce key concepts through repetition in a variety of formats.

- Universally Designed Assessments: Offer students choices in selecting topics and approaches for assignments or projects based on personal interest or relevance. This approach helps support individualized learning, foster creativity, and accommodate a broader range of skill sets.

- Flexible Assignment Formats: Provided similar learning outcomes are achieved, assignments can offer learners more than one way to demonstrate their knowledge, such as written essays, oral presentations, video presentations, infographics, or interactive projects. Giving students more than one way of fulfilling the assignment supports diverse learning styles and allows students to showcase their understanding in ways that align with their strengths.

As with last month’s examples, the strategies provided are by no means exhaustive. Tune in next month when we look at UDL strategies for reducing threats and barriers to learning!

Selected Resources:

3 Strategies for Removing Threats and Barriers

Removing threats and barriers to learning with Universal Design for Learning (UDL) involves incorporating teaching strategies and classroom activities to better meet the needs of all learners. Examples of barriers to learning may include a poorly constructed syllabus, little or no opportunity for collaborative work, learners’ lack of background knowledge in content, learners with second languages, lengthy exams, or one-shot, high-stakes, end-of-semester projects. There are some specific ways to implement UDL to remove these threats and barriers for learners and achieve the same learning outcomes. Try not to overwhelm yourself by attempting to implement all of these at once. Start small and gradually; try one or two strategies at a time. Understand this is an iterative process requiring self-reflection and evaluation: What worked, what didn’t, and why. The author and expert Thomas Tobin calls this “Plus One” Thinking in his book Reach Everyone Teach Everyone. Keeping a Plus One approach in mind, the following strategies offer examples of how to reduce or eliminate threats and barriers to learning.

1. Implement Engaging Learning Options.

Offer a variety of activities to support different interests and learning preferences.

This strategy reduces barriers to learning because it allows learners to choose content-related topics, projects, or activities that align with their strengths and course requirements. This also reduces threats and fosters a sense of community through collaborative learning opportunities. When learners share their perspectives and experiences, they gain a deeper understanding of the subject matter and become expert learners.

2. Diversify Representation in Your Presentations and Lesson Content.

Present information in multiple formats, such as text, audio, video, and graphics.

This strategy reduces barriers to learning by providing options for learners who use screen readers and other text-to-speech assistive technologies to access content. Interactive design bolsters learning, as does using different formats to present content, such as video, visuals, infographics, and gamification. Available tools like the Canvas built-in accessibility tool, built-in accessibility checkers for Office formats like Word and PowerPoint, and Adobe Acrobat’s PDF accessibility checker can help you ensure the content you author is accessible to diverse learners. SensusAccess converts inaccessible documents to a wide variety of more accessible alternate media formats, including audiobooks (MP3 and DAISY), e-books (EPUB, EPUB3, and Mobi), and digital Braille, as well as tagged PDF. EquatIO, a tool for making math content accessible, is available for free from the UIUC Webstore.

3. Address Action and Expression by Varying Testing and Assessment Methods.

Use a combination of written assignments, oral presentations, or multimedia projects.

This strategy reduces barriers to learning because scaffolded assessment methods, including formative and summative assessments, provide learners with different ways to demonstrate their learning progress and achievement. These can be high-stakes or low-stakes assessments. Variability in learners' cultural, linguistic, and disciplinary backgrounds affects their performance on different assessment types.

The strategies provided are by no means exhaustive. Tune in next month when we look at UDL strategies for fostering expert learners!

Fostering Expert Learners

Thus far, the CITL UDL Tip of the Month series has looked at the overall framework for UDL and considered a variety of course design strategies and applications for each of the three pillars of UDL: Multiple Means of Engagement, Representation, and Action and Expression. From this vantage point, this month’s tip examines the goal of UDL: supporting students to become expert learners.

What does it mean to be an expert learner? The Center for Applied Special Technology (CAST) defines “expert learners” as students “who are, each in their own way, purposeful and motivated, resourceful and knowledgeable, and strategic and goal driven.”* To unpack this definition a bit:

- Purposeful and Motivated Learners are goal-directed in their learning, set challenging learning goals for themselves, and know how to sustain the effort needed to achieve those goals.

- Resourceful and Knowledgeable Learners make connections to prior learning experiences and recognize the tools and resources to help them structure and retain new information.

- Strategic and Goal Driven Learners formulate plans for learning, monitor and reflect on their progress, and adapt their learning approaches based on feedback and new information, shifting strategies when necessary to achieve their goals.

In the context of design, the goal is to create learning environments that support all learners in becoming more expert-like in their learning approaches, regardless of their starting point or background. So, what course design strategies can be leveraged to help students become expert learners?

CAST offers the following 5 UDL Tips for Fostering Expert Learners along with examples and related design questions that instructors/designers can consider:

1. Support Relevant Goal Setting:

- Example: Inviting learners to reflect on a learning goal through personal experience or work they want to accomplish.

- Design Questions: Are the goals clear and relevant for my learners? How can I better support my learners to set their own relevant and meaningful goals?

2. Communicate High Expectations for All and Recognize Variability:

- Example: Using feedback that encourages all learners to believe they can achieve high expectations by acknowledging individual differences, communicating high expectations, and promoting goal-directed learning.

- Design Questions: Have I communicated consistent, high expectations for all learners? How have I supported my students to set high expectations for themselves? What resources have I made available to support learner differences?

3. Promote Disciplinary Expertise:

- Example: Clarifying the distinguishing features of disciplinary experts in your domain and highlighting how experts engage in their discipline.

- Design Questions: Have I defined and shared disciplinary expertise in my domain? In what ways are there opportunities for learners to become purposeful, resourceful, and strategic in different disciplines?

4. Focus on the Process, Not Just the Outcome:

- Example: Showcasing the steps that lead to a final product, such as editing drafts or discussing mistakes in a math problem.

- Design Questions: How do I highlight the learning process in my discipline? Am I offering mastery-oriented feedback throughout the learning experience?

5. Guide Self-Reflection:

- Example: Having learners share reflections about their learning frequently, with formative assessments like exit tickets, online feedback options, or journaling.

- Design Questions: Have I offered time for reflection about the learning process and how that process varies across disciplines? Where can I foster collaboration among learners to share about their learning processes? How do I model the process of expert learning for learners?

Ultimately, becoming an expert learner is an ongoing learning process that is reflective and evolving. By understanding and implementing design strategies that support students in becoming purposeful, motivated, resourceful, and strategic in their learning, instructors and designers can create inclusive learning environments where all students can thrive. The 5 UDL tips provided offer practical guidance for designing courses that not only accommodate diverse learners but also empower them to become expert learners, capable of navigating and succeeding in any learning context.

* Adapted from CAST (2017). UDL Tips for Fostering Expert Learners. Wakefield, MA: Author. Retrieved from https://www.cast.org/products-services/resources/2017/udl-tips-fostering-expert-learners

UDL-ify Your Syllabus: Engagement

This is the first in a three-article series of UDL Tips focused on applying UDL principles to your syllabus. Some people think they can only use UDL principles in the classroom or the online course, but it is not necessarily so. UDL principles are designed to apply to any situation beyond the classroom or online course, such as the syllabus. The syllabus is an important document that cannot be ignored or overlooked; some instructors lament that their students don't pay attention to their syllabus or don't understand why some students complain that the syllabus is too complex to follow or overwhelming. Some students get turned off or offended by the tone or language.

You'll be surprised how easy it is to improve (or UDL-ify) your syllabus using the UDL principle of Engagement to increase students' interaction and motivation with the syllabus's contents and choices for learning opportunities.

Syllabus Dynamics

Before we analyze or scrutinize the syllabus, we need to understand its "dynamics" and how it affects your students' perception in a positive or negative light. You want your syllabus to give a positive first impression the first time to motivate your students to do well in your course. The dynamics involve a contract, instructional tool, course climate, and first-time impression. The syllabus is more than just a document; it's a contract, a binding agreement between the instructor and students. Students need to recognize this and take it seriously, as it sets the framework for the course and their responsibilities.

Clear Instructions

Use plain language instead of contractual language to communicate so they understand and use the information to meet their goals. Plain language means to communicate “with clear wording, structure, and design for the intended audience to easily:

- find what they need

- understand what they find

- use that information.[1]

Syllabus as Instructional Tool

Secondly, the syllabus should be treated as an instructional tool; it guides students' learning as they read the syllabus. There should be no guesswork if the instructions are not clearly stated or if the acronyms or abbreviations are not understood. Spell out the term and add the acronym or abbreviation at the end of the term for the first time, e.g., anthropology (ANTH). After that, use the abbreviation.

Course Climate and First Impressions

Thirdly, course climate always starts with the syllabus because it sets the tone for the entire semester; the use of inclusive language or tone is critical for retaining students. It is about being respectful and nonjudgmental, creating a safe and positive learning environment for everyone involved. Look for any assumptions or attitudes you have about your students and work on removing them and making it more inclusive. Lastly, the syllabus's first impression either makes it or breaks it. It hinges on how you use the language or tone. Is it:

- cold or warm?

- commanding or inviting?

- paternalistic or cooperative? [2]

For more information, read Rhetoric in the footnote. It's natural for everyone to want to pass the first impression. The syllabus should be the priority to ensure it passes the first impression before sharing or posting it in class. Consider the dynamics, such as contractual language, clear instructions, course climate policy, etc., in your course syllabus and see how to make it more interactive and motivational. Make it engaging. Ask your colleague to review your syllabus or survey your class for suggestions or ideas at the end of the semester.

If you're interested in consulting with CITL's UDL Team on your syllabus or other UDL-related matters, please see our Contact information below. In the meantime, tune in next month when we focus on applying the UDL principle of multiple modes of representation to your syllabus!

Image credit: Seattle Central College. (October 12, 2011). Universal Design. Retrieved from https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=4FE1CLS7i3k

[1] Accessible Syllabus. Rhetoric. Retrieved from https://www.accessiblesyllabus.com/rhetoric/

[2] Center for Plain Language. Five Steps to Plain Language. Retrieved from https://centerforplainlanguage.org/learning-training/five-steps-plain-language/

UDL-ify Your Syllabus: Representation

This article is the second in a three-article series of UDL Tips focused on applying UDL principles to your syllabus. The first article (The April 2024 tip of the month) focuses on Engagement and how it influences students' interactions with the syllabus contents and choices for learning opportunities. This article looks at how representation impacts students' retention and comprehension through visual learning style, language, and symbols. These multiple modes help students learn more actively and pay greater attention to the syllabus by providing them with a variety of ways to access course content and resources. While the time-honored tradition of starting a course with a syllabus quiz and the imperative to "Read the Syllabus!" may have a certain brute force effectiveness, it does little to establish a welcoming learning environment and does not reflect the principle of multiple modes of representation. Here's how you can UDL-ify your syllabus using the principle of representation to give your students multiple avenues for accessing your course content.

Digital Formats

Let’s start with digital formats. Providing a digital syllabus allows students the flexibility to obtain information in a different medium and may be especially helpful for students who may be using assistive technology like screen readers and other text-to-speech software. A digital syllabus can give students the option to listen on mobile while driving or exercising or to modify the text or colors for better readability. Start by offering two different formats in your course:

- Add a Syllabus page in Canvas.

- Post a Word document attachment.

- Post a digital syllabus in Google Drive.

- Create a video syllabus.

Word or Google documents can be printed or modified. And if you’re making a video, a little creativity can go a long way—for instance, using a slideshow with audio or touring different parts of the syllabus to explain or highlight the text or images. The sky’s the limit!

Visual Content

Seeing visual content also helps people remember better than reading or listening to text alone because our brain needs more processing time to perceive words as tiny pictures and then identify features of letters before we can read them. Combining auditory and visual cues increases the percentage of remembering the information over the text alone. John Medina, a biologist who studies the brain, found that people remember visually 65%![1]

Here are a few ways to illustrate your syllabus visually:

- Highlight with colors, symbols, or icons.

- Use lists to summarize or highlight key points.

- Use data tables to organize course schedule, office hour information, etc.

- Use meaningful images that convey the content.

Before jumping in, take a few minutes to review your syllabus and consider how you can modify and organize the information to better suit visual learners. This small adjustment can make a big difference in their learning experience.

Resource Types

Lastly, consider offering a variety of resource types, rather than the required textbook alone. Offering students multiple modes of representation increases the possible ways they can understand the subject matter and improves retention. Why not change the pace and help your students feel a little less daunted by the required textbooks? Change up your approach by making greater use of different multimedia, books, and other formats. Let your class:

- Search textbooks online.

- Choose one of two textbooks offered.

- Access textbook information via paper, electronic formats, audio, etc.

These are just a few ways you can improve your syllabus with small changes that offer multiple representations of content that engage students' retention and comprehension through visual learning style, language, and symbols. If you would like more information or a consultation on this topic, CITL’s UDL Team is here to help. You can reach us at mailto:CITL-UDLTeam@illinois.edu. In the meantime, stay tuned for next month's article on how to apply multiple modes of action and expression to your syllabus.

References

Boyle, Molly. Think College. (2010). Six Tips for Building a Universally Designed Syllabus. Retrieved from https://thinkcollege.net/resource/universal-design-learning-udl/six-tips-building-universally-designed-syllabus

Image credit: Seattle Central College. (October 12, 2011). Universal Design. Retrieved from https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=4FE1CLS7i3k

Image credit: Inayaysad, CC BY-SA 4.0, via Wikimedia Commons

[1] John Medina. Brain Rules. Retrieved from https://brainrules.net/vision/

UDL-ify Your Syllabus: Action and Expression

This is the third and final article in our three-series focused on applying Universal Design for Learning (UDL) principles to your syllabus. The first article focused on Engagement (The April 2024 tip of the Month); the second article examined Representation (The May 2024 tip of the month). The third principle, Action and Expression, provides multiple modes for students to express or demonstrate course learning through different outputs or assessments. You may wonder how you could cater to your students' needs by applying the UDL Action and Expression principle to the syllabus. UDL principles are designed to work with all course contents (e.g., syllabus, rubric, learning activities, etc.). As you read on, you may just have an "Aha!" moment. Let's examine some options for offering multiple means of Action and Expression.

Offering Multiple Options for Action and Expression

When we think of the principle of doing something or expressing ourselves, we give our students options or alternatives for how they want to interact with the course contents through the assignments or projects. This approach requires a creative mindset, as we need to offer options while adhering to the course and activity objectives. The requirements are necessary to give the projects and assignments structure; adding options to the requirements will remove barriers for those with invisible disabilities or for people for whom English as a second language, for instance. However, all students benefit from the UDL principle of multiple means of action an expression regardless of abilities because they are given more freedom to learn and express themselves. For example, instead of requiring learners to present orally (i.e., traditional oral presentation), why not think outside the box and allow them to consider choices like the following:

- Play (role-play)

- Movie/video

- Puppet show

- Poster session

- Games (Jeopardy! or Crossword)

Alternatives in Addition to the Traditional Term Paper Assignment

The list of choices above allows students to choose an activity to put into action or to express. UDL allows for alternatives that better meet the needs of learners with differing abilities or circumstances. For example, instructors often require all students to write a term paper as the only option, creating barriers for some students. Instead of only offering a term paper option, why not let learners demonstrate their knowledge in other ways. Some ideas are:

- Concept or mind mapping

- Photo slideshow or visual analysis paper

- Animations

- Wiki platforms, web page, or website

These ideas give you a great start to think about your course, and this is just the tip of the iceberg. There are other opportunities where you can UDL-ify your course with the principle of Action and Expression in mind. While oral presentation and term papers are traditional ways of assessing and shouldn’t be abandoned altogether, consider asking yourself, “What changes can I make for students to demonstrate what they have learned but in different ways?” Small changes work wonders, and your teaching techniques improve. You will be amazed at how excited your students will be when they see alternatives in the syllabus. Enhance your students’ learning opportunities by guiding them through multiple modes of Action or Expression as they share their knowledge differently.

Embracing Learner Variability

In every classroom, students bring unique experiences, strengths, and challenges. They differ in how they engage with learning, construct meaning, and express what they learn. In the context of Universal Design for Learning (UDL), this is what we refer to as “learner variability.” Recognizing there is no one-size-fits-all approach to teaching, the UDL framework provides a way to design learning experiences that are flexible and adaptable to meet the diverse experiences, strengths, and challenges of students.

Why Does Learner Variability Matter?

Research shows that each human brain is as unique as a fingerprint. Factors like genetics and life experiences shape how individuals learn, and these differences continue to evolve throughout life. Teaching methods that assume all students learn the same way often leave some students disengaged. UDL-based instruction designed with flexibility in mind can help address the natural variability among learners. This is backed up by several studies that show UDL-based strategies increase student engagement and improve academic achievement. By recognizing learner variability, we can better engage students and improve outcomes for all learners.

Practical Strategies for College-Level Instructors

Here are a few UDL strategies to incorporate learner variability into your teaching:

- Offer Multiple Means of Engagement: Not all students engage with material in the same way. Some prefer active discussions, while others might need time to reflect individually. Consider providing different ways to engage, like offering both synchronous and asynchronous discussion options.

- Present Content in Multiple Formats: Use diverse media to present material. Combine readings, videos, infographics, and hands-on activities where appropriate. This allows students to choose formats that align with their strengths.

- Provide Flexible Assessment Options: Assessments don’t have to be one-size-fits-all either. While exams might work for some, other students might excel with projects, presentations, or portfolios. Allowing students to demonstrate learning in different ways can improve engagement and outcomes.

- Encourage Reflection and Goal Setting: Help students take ownership of their learning by incorporating opportunities for reflection. Encourage them to set learning goals and monitor their progress throughout the course, fostering a sense of agency and self-direction.

Final Thoughts

By embracing learner variability and incorporating UDL strategies, you can create an inclusive and supportive learning environment that fosters success for all students. However, it is important to remember that while Universal Design for Learning (UDL) strategies optimize the learning experiences for students by recognizing learner variability and reducing barriers to learning, UDL does not replace the need for individualized accommodations, assistive technologies, and supports that remain essential for ensuring students receive equitable opportunities tailored to their unique learning needs. In short, both strategies are essential for inclusive education.

For Further Reading

Capp, M.J. (2017). The effectiveness of universal design for learning: A meta-analysis of literature between 2013 and 2016. International Journal of Inclusive Education, 21(8), 791-807.

Ok, M. W., Rao, K., Bryant, B. R., & McDougall, D. (2017). Universal Design for Learning in pre-k to grade 12 classrooms: A systematic review of research. Exceptionality, 25(2), 116-138.

Pape, B. (2018). Learner variability is the rule, not the exception. Washington, DC: Digital Promise Global. Retrieved from https://digitalpromise.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/06/Learner-Variability-Is-The-Rule.pdf

Addressing Learner Variability in Your Classroom

Note: This Tip of the Month article is the second in a two-part series on Learner Variability.

Consider the barriers a learner may encounter in your course due to the content as well as the current design of your course. Consider how the delivery method (face-to-face, online, blended, hybrid) impacts learner variability and magnifies or reduces barriers to learning they may encounter.

Learner Variability Explained

“Learner Variability” is the term used to describe how unique and varied students are in the ways they interact with content. For example, no two learners activate the same pathways in the brain. As you think about the variability of learners in your courses, it may be helpful to consider their individual learning profiles (Rose, 2016). Doing so gives us a broader way of describing the range of a learner's strengths and needs. Consider how you would intentionally build flexibility into your course to support the areas of need and bolster the areas of strength.

Barriers (Needs) that Affect Your Students

- Second or Native language

- Disability

- Background knowledge in course topics

- Access

- Interest in course topics

- Study habits

- Ability to organize and plan

- Creativity

- Attention and retention

- Remembering and recall

- Reading

- Writing vs. verbalizing ideas

- Self-regulation

- Executive function

- Persisting or persevering

- Stressors and anxieties

What Can You Do?

Commit to addressing at least one anticipated area of learner variability in the design of one of your courses. Making small changes using a gradual and deliberate process helps make what could feel like a very large undertaking more manageable (Tobin, 2018).

References

- Digital Promise. (n.d.). “Learner Variability Navigator.”

- Rose, T. (n.d.).“Todd Rose on learner variability” [Video]. YouTube.

- Tobin, T. (2018). Reach Everyone, Teach Everyone: Universal Design for Learning in Higher Education. West Virginia University Press.

"Clear Goals, Multiple Means”

When designing your course, one of the most powerful ways to make learning more inclusive and engaging is by clearly stating your learning goals and offering multiple means for students to achieve them. Practically a mantra in the UDL world, “Clear Goals, Multiple Means” underscores the importance of clearly defining what students need to accomplish while offering flexibility in how they get there. This approach makes learning more inclusive and engaging by empowering your students to make choices that maximize their strengths and support their learning preferences.

Content-based Goals

With content-based goals where the focus is on understanding the content, multiple means can open avenues for your students to explore a topic in a variety of ways. For instance, if the goal is to “analyze how early jazz shaped social and cultural movements,” you might offer students multiple ways to explore the impact of jazz music. Students could examine how jazz challenged social norms in the early 20th century, promoted cultural expression, and sparked movements in art, dance, and fashion. They could look at how jazz spread globally, shaping music traditions worldwide, or analyze its role in advancing civil rights or breaking down racial barriers. To meet this goal, students might choose to write an essay, create a multimedia timeline showing jazz’s influence on different art forms, or produce a video or podcast discussing jazz’s role in social justice movements. The possibilities here are rich and, in the spirit of Thomas Tobin’s +1 model, can be expanded in an iterative, reflective, and evolving manner.

Skills-based Goals

For goals that are more skills-based, it’s important to offer multiple means for students to practice and to demonstrate the relevant skills. For example, in a business course focused on data analysis, a clear, skills-based goal might be to "use spreadsheet software to analyze data sets and present findings through visualizations." To meet this goal, you could offer multiple means for students to practice. Some might prefer watching a video tutorial, while others might prefer following step-by-step written instructions or a live demonstration during office hours. For assessments, you could also allow students to demonstrate their spreadsheet analysis and data visualizations in different ways: a written report with charts, a recorded walkthrough of their data analysis process, or a live presentation. The more flexibility you offer, the more students can engage with the material in ways that align with their learning preferences and strengths.

In a nutshell, by designing with clear goals and multiple means in mind, you’re creating a learning environment that respects, and provides for, students’ diverse ways of engaging with content and demonstrating their knowledge. This approach not only makes learning more inclusive and impactful—it also encourages students to take ownership of their learning, fostering greater independence and confidence on their pathway to becoming what UDL educators commonly refer to as “expert learners.”

Resources

- IRIS Center. (2024). Goals. Vanderbilt University.

- CAST. (2020). UDL Tips for Developing Learning Goals (PDF).

Building Bridges: UDL and Instructional Scaffolding

Have you ever wondered how Universal Design for Learning (UDL) and instructional scaffolding might work hand-in-hand to support your students? “Instructional scaffolding” is a process in which an instructor provides targeted support to guide and enhance students' learning, systematically building on their prior experiences and knowledge as they master new skills, with the support gradually removed as they gain competence.1 In this context, you might think of UDL as the "architect" of an inclusive learning environment and scaffolding as the "contractor" who provides the supports needed to help students build their skills, understanding, and confidence. Together, UDL and instructional scaffolding create a learning space where students have the tools they need to succeed, regardless of their starting point.

Zone of Proximal Development

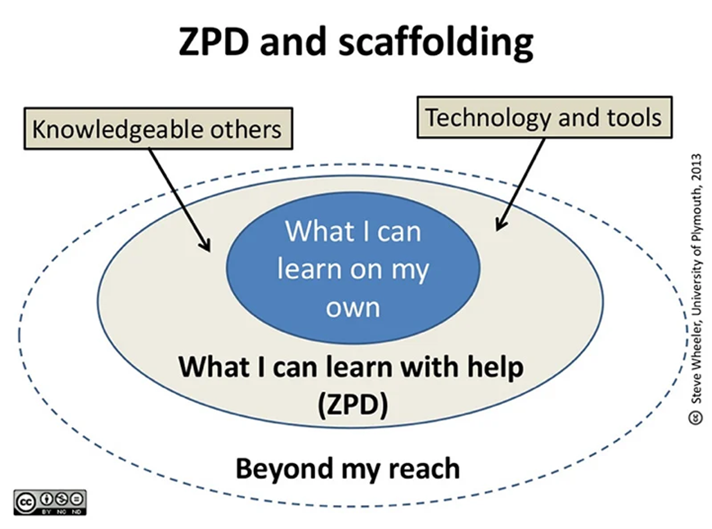

Underpinning this synergy between UDL and scaffolding is what Russian psychologist Lev Vygotsky identified as the Zone of Proximal Development (ZPD): the idea that students learn best when working on tasks just beyond their current abilities, provided they receive appropriate guidance and support (see Figure 1). While UDL helps create the foundation for inclusion by ensuring that materials, tasks, and assessments are designed to meet diverse needs, the scaffolding connects directly to this by offering timely, responsive supports that help students navigate their ZPD and move gradually toward greater understanding and independence.

Figure 1: Vygotsky's Zone of Proximal Development2

Instructional Scaffolding

For example, in an online sociology course, learning how to conduct field observations might involve offering tutorials in multiple formats (videos, PDFs, interactive guides, etc.) and giving students flexibility in how they present their findings (written reports, infographics, video presentations, etc.). The scaffolding can build on this framework by providing step-by-step worksheets to structure learners’ observations, modeling the process, pairing students with a peer for their first site visit, and then ultimately conducting a field observation on their own.

To give you an idea of some of the activities and tools that can serve as instructional scaffolding, here’s a list of 10:

- Graphic Organizers – Visual tools to help organize and structure information.

- Worksheets and Checklists – Step-by-step instructions that break down complex tasks and guide students through a process.

- Low Stakes Learning Checks – Short quizzes or activities to help reinforce key ideas and concepts

- Guiding Questions – Questions that direct students’ thinking and focus attention on key concepts.

- Modeling – Demonstrating a task or process for students to observe and learn from.

- Scaffolded Reading – Providing reading materials at varying levels of complexity with supports like annotations or glossaries.

- Concept Maps – Visual representations of the relationships between concepts.

- Video Tutorials – Instructional videos to visually guide students through tasks or concepts.

- Peer Collaboration – Structured group work that encourages students to help each other.

- Rubrics – Clear guidelines for expectations and assessment of student work.

Ultimately, combining UDL with thoughtfully constructed instructional scaffolding can go a long way in addressing learner variability, fostering greater independence, and creating expert learners. While scaffolding helps students progress within their zone of proximal development and build competence, UDL ensures these supports are designed to meet diverse needs. Throughout the process, students gain confidence, develop self-regulation, and acquire the adaptability they need to become expert learners who are purposeful, motivated, and resourceful.

References

- IRIS Center. (2024). Providing instructional supports.

- McLeod, S. (2024, August 9). Vygotsky’s theory of cognitive development. Simply Psychology.