Inclusive Course Design

1.1 Inclusive Course Design

Why is it important?

Inclusion ensures that diverse perspectives are viewed as assets and that teaching methods are adaptable to meet students' varied needs. Estefan et al. (2023) identified academic readiness, access to resources, including time, money, and technology, and social biases as three major structural barriers affecting student performance in college. In the article, Estefan discusses the importance of leveraging students' previous knowledge to promote transformative translation, which refers to the active process by which an individual undergoes a deep, structural shift as they process new information (Estefan et al., 2023; Kokkos, 2022). Dazeley et al. (2024) suggest that using an Agile Backwards Design in course development can allow students to leverage their knowledge and experiences as they learn new material in a course.

How can we implement it?

Start by identifying the course's primary purpose and objectives. Write clear, actionable, and measurable goals and objectives using an ABCD or SMART approach. Take some time to think about who your students are and what motivates students to take the course. Reflect on any assumptions about students’ prior knowledge and access to materials and how these might influence their performance in the course. Using an inclusive backward design approach, create a roadmap to guide students from their starting point to the final course goals. Identify major milestones and assessment tools to evaluate student progress toward those goals at each milestone. Consider using varied, frequent, and low-stakes assessment strategies and intentionally incorporating ways to connect with your students throughout your course to support student learning and create a positive classroom climate.

Reference

Araujo Dawson, B., Kilgore, W., & Rawcliffe, R. M. (2022). Strategies for creating inclusive learning environments through a social justice lens. Journal of Educational Research and Practice, 12(0), 3-27. https://doi.org/10.5590/JERAP.2022.12.0.02

Dazeley, R., Goriss-Hunter, A., Meredith, G., Sellings, P., Firmin, S., Burke, J., & Panther, B. (2024). Agile backward design: A framework for planning higher education curriculum. Journal of Educational Research, 133(84), 772-787. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13384-024-00772-7

Estefan, M., Cordes Selbin, J., & Macdonald, S. (2023). From inclusive to equitable pedagogy: How to design course assignments and learning activities that address structural inequalities. Teaching Sociology, 51(3), 262-274. https://doi.org/10.1177/0092055X231174515

Kokkos, A. (2022). Transformation theory as a framework for understanding transformative learning. Adult Education Critical Issues, 2(2), 20-33. https://doi.org/10.12681/haea.32541

Wijngaards-de Meij, L., & Merx, S. (2018). Improving curriculum alignment and achieving learning goals by making the curriculum visible. International Journal for Academic Development, 23(3), 219–231. https://doi.org/10.1080/1360144X.2018.1462187

Resources 1.1: Inclusive Course Redesign

Checklist for this section:

- Primary purpose and objectives

- ABCD or SMART approach

- Who your students are

- What motivates students

- Students’ prior knowledge and access

- Inclusive backward design

- Milestones

- Assessment tools

- Varied, frequent, and low-stakes assessment strategies

- Connect with your students

Primary Purpose and Objectives

| Purpose/Objectives | Description |

|---|---|

| Purpose | It is a broad statement that outlines the overall aim or intention of the course within the university's curriculum. It describes what the course is designed to achieve in a general sense. |

| Objectives | They are specific, measurable statements detailing what students should know or be able to do by the end of the course. They break down the course purpose into actionable and assessable components. |

Different factors influence the course's purpose and objectives. Most of these are dictated by the course role in the curriculum. General education courses must meet the requirement for General Education Learning Outcomes. Similarly, transferable courses must consider Articulation Agreements such as those described by the Illinois Articulation Initiative (IAI), and prerequisite courses must meet the demands of the future courses in the sequence. Before deciding on a course's purpose and goals, consider the course's role within the curriculum.

Course Purpose

College courses serve various purposes, each designed to allow learners to develop academically, personally, and professionally:

| Purpose | Description | Yes | No |

|---|---|---|---|

| Prerequisite Courses | These courses focus on proving the foundational knowledge and skills necessary to succeed in higher-level courses. They also ensure that students are well prepared for the new academic content ahead. | O | O |

| Core Courses | These are mandatory courses within a major that provide essential knowledge and skills related to the field of study. | O | O |

| Elective Courses | These courses allow students to explore interests outside their major, providing flexibility and a broader educational experience. | O | O |

| General Education Courses | These courses cover many subjects, promoting a well-rounded education and cultivating students’ necessary skills such as critical thinking, communication, and quantitative reasoning skills. | O | O |

| Cultural Awareness Courses | These courses focus on understanding and appreciating diverse cultures, fostering social skills and global awareness. | O | O |

| Laboratory and Clinical Courses | These courses provide hands-on, practical experience that is essential for developing the skills and knowledge needed for professional practice in scientific and healthcare fields. | O | O |

| Capstone Courses | These are advanced courses typically taken in the final year, designed to integrate and apply knowledge from the entire program in a comprehensive project or research. | O | O |

*Courses might fall into more than one category.

Course purpose and objectives examples

| Course | Goal | Learning Objective |

|---|---|---|

| Intro to Psychology | To provide students with a comprehensive overview of psychology's major concepts, theories, and research findings. | Introduction to Psychology:

|

| Organic Chemistry | To prepare students for advanced studies in chemistry and related fields by understanding organic compounds' structure, properties, and reactions. | Organic Chemistry:

|

General Education Course Objectives

The General Education Assessment ensures the quality and effectiveness of the university's education through a systematic process to evaluate and improve general education. The assessment focuses on four key thematic outcomes: Foundational Knowledge, Contextual Knowledge, Inquiry Skills, and Application Skills.

| Thematic Outcome | Description |

|---|---|

| Foundational Knowledge | Students will be able to explain the fundamental concepts, theories, knowledge, and perspectives of a particular discipline. |

| Contextual Knowledge | Students will be able to analyze concepts, issues, or human experiences within or across contexts. |

| Inquiry Skills | Students will be able to use information or methods to investigate a question or problem and draw an interpretation. |

| Application Skills | Students will be able to communicate and apply subject matter knowledge to new contexts and problems. |

For more information, visit: General Education Assessment – Office of the Provost

ABCD or SMART Approach

ABCD stands for Audience, Behavior, Condition, and Degree. Often, learning objectives are written in order of Condition, Audience, Behavior, and Degree (CABD). This ABCD approach helps instructors identify effective assessment tools for evaluating student learning:

ABCD approach when crafting clear and measurable learning objectives:

- Audience: Defines who the students are.

- Behavior: Includes what students will do or expected to do.

- Condition: Sets the context or tools that students are given.

- Degree: Specifies how well the task be performed.

Below are five learning objectives examples:

| Discipline | Example |

|---|---|

| Psychology | Given a case study on cognitive development (condition), undergraduate psychology students (audience) will be able to analyze the developmental stages (behavior) using all stages of Piaget's theory of cognitive development (degree). |

| Biology | After completing the lab on cellular respiration (condition), biology majors (audience) will be able to explain the process and its significance (behavior) in a detailed written report graded at a B level or higher (degree). |

| History | Given primary and secondary sources on the Civil Rights Movement (condition), history students (audience) will be able to compare and contrast different perspectives (behavior) in a 5-page essay with proper citations (degree). |

| Business | Using customer data (condition), business students (audience) will be able to develop a comprehensive marketing strategy (behavior) that receives at least an 85% customer approval rating (degree). |

| Computer Science | Given a set of programming problems (condition), computer science students (audience) will be able to write and debug code in Python (behavior) with no more than two errors per program (degree). |

SMART approach when crafting assignment expectations:

- Specific: Clearly defines what students are expected to achieve.

- Measurable: Includes criteria that allow for assessment of student performance.

- Achievable: Sets realistic and attainable goals for students.

- Relevant: Aligns with the broader course objectives and student learning needs.

- Time-bound: Specifies a timeframe within which the objective should be met.

Learning Objective Example with SMART approach:

“By the end of this assignment (time-bound), students will be able to analyze and interpret the central themes of a selected literary work (specific) and construct a coherent argument supported by textual evidence (measurable). The goal is for students to enhance their critical thinking and analytical writing skills (achievable), aligning with the course objective of developing advanced literary analysis capabilities (relevant).”

Who are your students?

| Are your students … | Yes | No |

|---|---|---|

| … freshmen? Sophomores? … Mixed? | O | O |

| … full-time students? | O | O |

| … financially stable? | O | O |

| … academically prepared? | O | O |

| … socially prepared? | O | O |

| … food secured? | O | O |

| … supported by others? | O | O |

| … providing support to others? | O | O |

| … physically able? | O | O |

| … cognitively able? | O | O |

| … connected to the university or college? | O | O |

| … connected to any student resources? | O | O |

University of Illinois resources to help you know your students:

- Division of Management Information (Institutional Research) (illinois.edu)

- Division of Management Information (Institutional Research) (illinois.edu)

- Chancellor’s Senior Survey

- Illini Success

- Degrees Awarded

- Workbook: 10 day Dashboard Fall 2024

What Motivates Students

Understanding students’ motivations for taking a course can help instructors tailor instruction to foster an engaging and supportive learning environment.

Here is a list of common motivators:

| Motivator | Strategy for Engagement |

|---|---|

Advancement Better job opportunities and career advancement | Career-Focused Assignments: Design assignments that allow students to gain firsthand field experience that can be added to their resume. Guest Speakers: Connect students with professionals from relevant industries to speak about their career paths and the importance of the course material in their jobs. |

Finances Higher earning potential and financial security | Case Studies: Integrate activities and case studies that highlight the job market potential and other benefits associated with the field. Alumni Success Stories: Through short videos, case studies, etc., share stories of “successful” alumni and highlight the role of the course in their development. |

Growth Improve or develop a specific soft or technical skill | Hands-On Activities: Integrate field tools and software (e.g., data analytics tools for a business class) into coursework. Real World Project: Incorporate real-world projects like developing a mobile app or a website. This hands-on experience can spark interest and show the practical applications of coding skills. |

Subject Innate interest in the course or field. | Community engagement: Promote student involvement in local projects (e.g., local conservation projects for an environmental science course). Individual development: Allow students to engage with the material beyond the class (e.g., conducting an independent research project). |

Social Taking a class with a friend | Group activities: Encourage group projects or discussion activities where friends can collaborate on researching or reviewing the topics (e.g., debates, collaborative art projects, study groups). Gaming: Incorporate gamification strategies where students can compete together or against each other (e.g., coding challenges or hackathons for a computer science course, lab-based competitions for a science course, or simulation games for a business course). |

Students Prior Knowledge and Access

Consider what type of knowledge and skills you assume students have before entering your course that might influence their engagement and performance. Consider the following question:

What assumptions do I have about the students entering my course regarding [AREA], and how might those influence their performance in the course?

| Area | Example |

|---|---|

| Academic | Background knowledge (math, writing, reading, citing, formatting, etc.) |

| Soft Skills | Communication, teamwork, time management, critical thinking, adaptability, motivation, etc. |

| Cultural | Background and experiences, language proficiency, family structure, value, etc. |

| Physical | Uniform physical ability, cognitive impairment, physical impairments, independence, etc. |

| Engagement | Interest, oral participation, time allocation to the subject, extracurricular involvement, etc. |

| Social | Support networks (family, friends, peers, etc.), access to resources, help-seeking behavior, etc. |

| Experiential | Cultural exposure (understanding of certain sports, events, holidays, etc.), field experience, academic culture, etc. |

| Technical | Technology proficiency, access to technology, digital literacy, etc. |

Inclusive Backwards Design

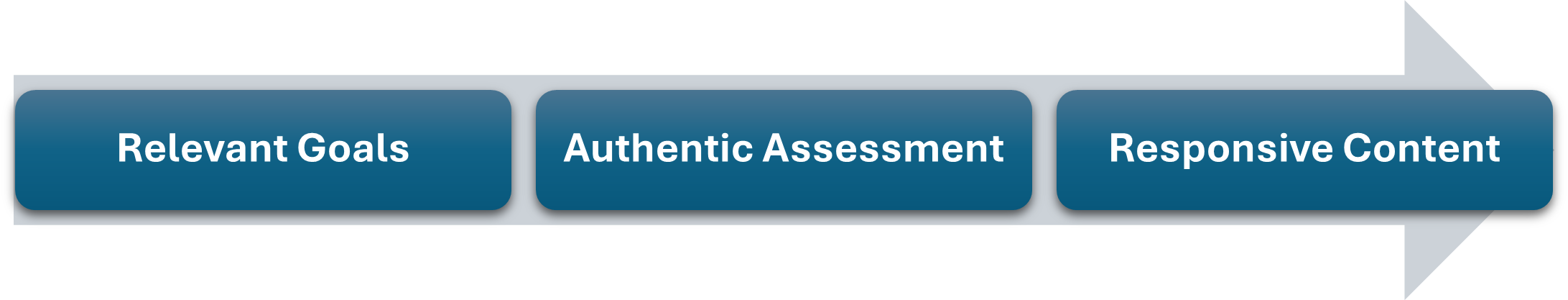

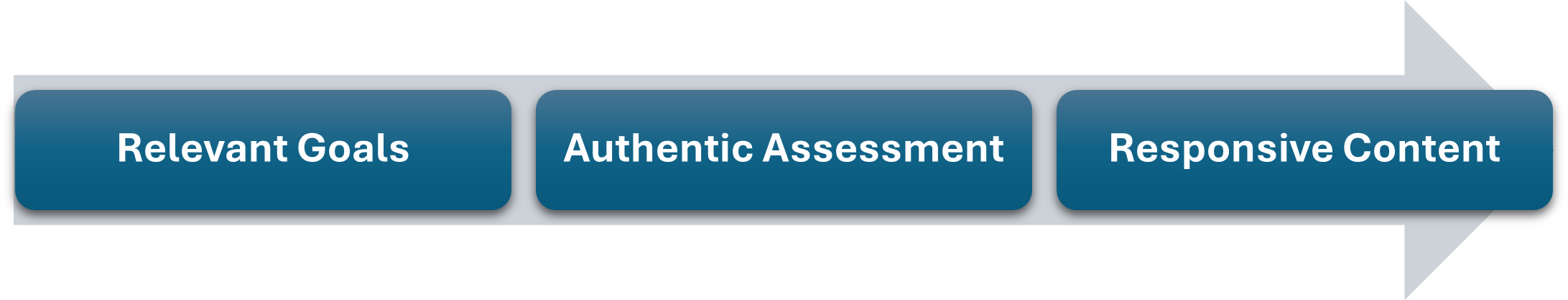

Combining inclusive practices and backward design allows faculty to strategically create courses that support inclusive learning. Backward design starts by identifying course goals and objectives, followed by identifying assessment strategies and tools to assess student progress toward the course objectives and goals. In an inclusive backward design framework, we aim to create goals that are relevant, assessments that are authentic, and content that is responsive to our students’ wealth.

| Concept | Description |

|---|---|

| Relevant Course Learning Goal | This refers to a specific, measurable objective that aligns with the overall aims of a course and is meaningful to the student’s academic and professional development. |

| Authentic Course Assessments | These are evaluation methods that require students to apply their knowledge and skills in real-world or realistic scenarios. Authentic assessments often involve tasks such as projects, presentations, or practical applications that mirror the challenges students might face in their future careers rather than traditional tests or quizzes. |

| Responsive Course Content | This involves designing and delivering course materials that are adaptable to the needs, interests, and feedback of students. Responsive content is flexible and can be adjusted based on student performance, engagement, and evolving educational standards, ensuring that the learning experience remains relevant and effective. |

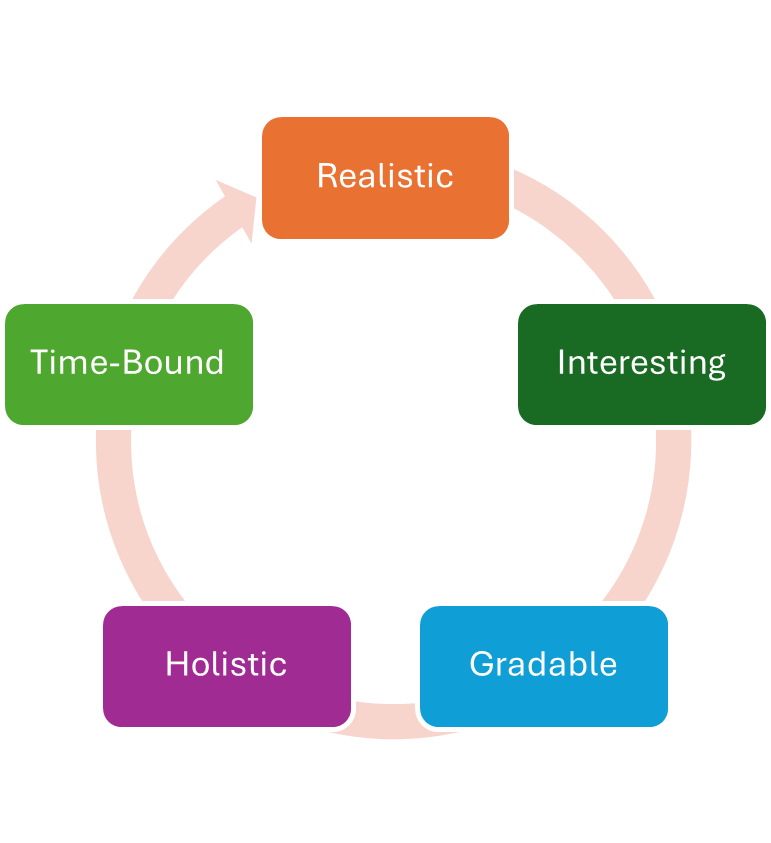

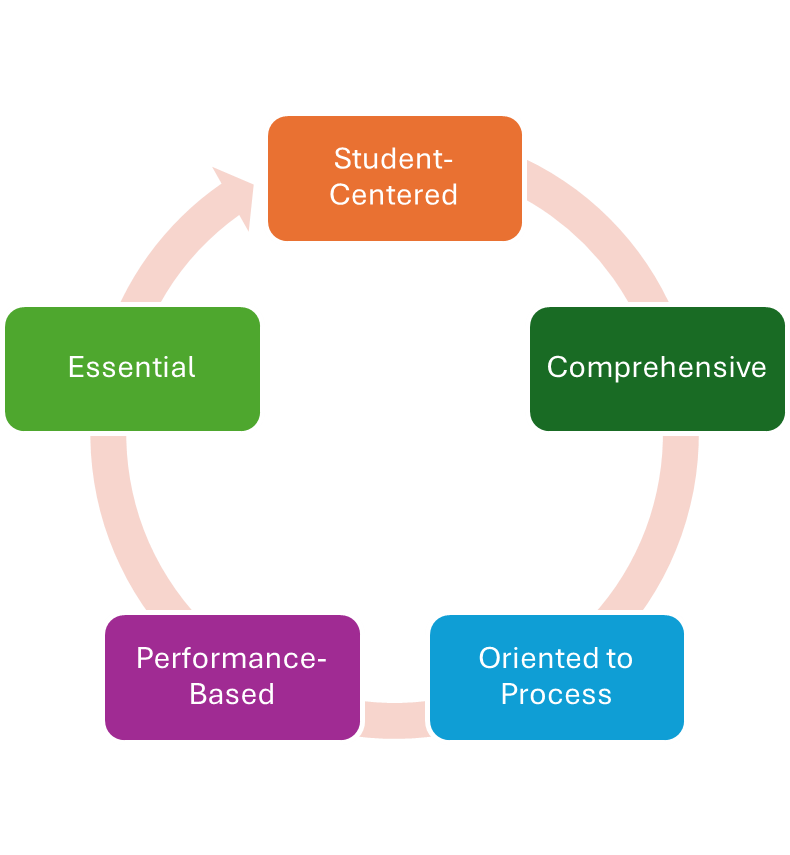

Inclusive practices suggest learning objectives to be:

- Realistic: Goals should be achievable and practical, considering the resources, time, and constraints of the course. They should challenge students but still be attainable with effort and support.

- Interesting: Goals should engage and motivate students by being relevant to their interests and future aspirations. They should spark curiosity and encourage active participation in the learning process.

- Gradable: Goals should be measurable and assessable, allowing instructors to evaluate student progress and achievement. Clear criteria and standards should be established to ensure fair and consistent grading.

- Holistic: Goals should address multiple aspects of student development, including cognitive, emotional, and social dimensions. They should promote a well-rounded education that goes beyond mere content knowledge.

- Time-Bound: Have specific deadlines or time frames to provide structure and urgency. This helps students manage their time effectively and stay on track throughout the course.

Inclusive practices suggest assessment strategies:

- Aim to assess students’ abilities in ‘real-world’ contexts.

- Focus on applying knowledge and skills to practical, meaningful tasks.

- Student-Centered: Students often have a role in designing the assessment tasks, which can increase engagement and motivation.

- Comprehensive: Assessments often involve scaffolding of sections to allow for responsive feedback and intentional growth.

- Oriented to Process: Emphasis is placed on the learning process, including planning, research, and reflection, not just the final product.

- Performance-Based: Students demonstrate their knowledge and skills through projects, presentations, experiments, or other hands-on activities.

- Essential: Tasks are designed to reflect real-life challenges and applications.

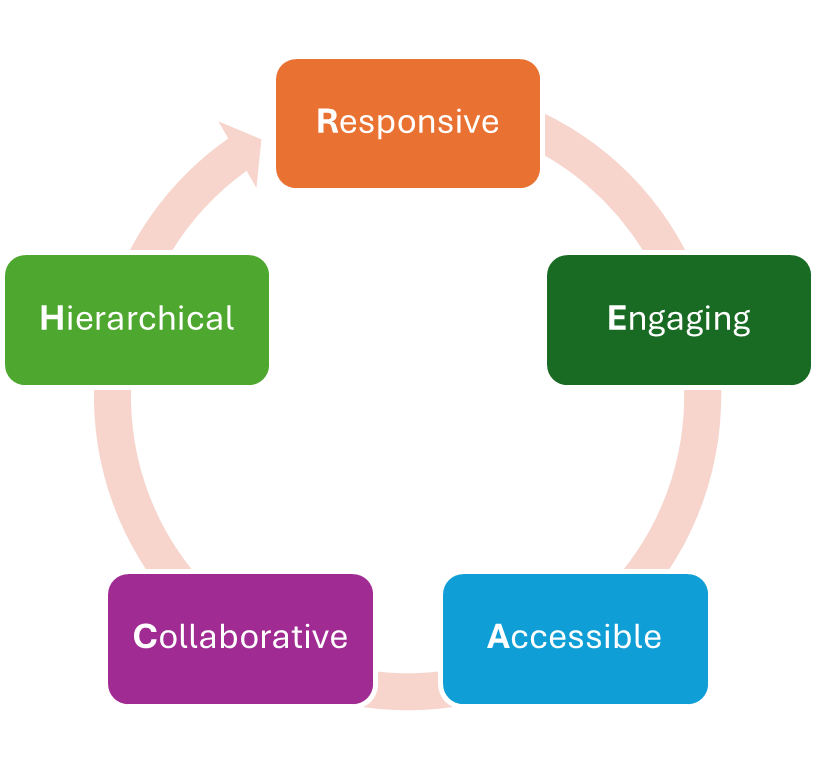

Content delivery must align with the assessment strategies in place. Instructional materials and activities must be designed to help students prepare and succeed in their assessments. Instructional materials and activities must be developed to be:

- Responsive: Adapts to the needs, preferences, and feedback of students.

- This includes being flexible in delivery methods, adjusting to different learning paces, and incorporating student input to make the learning experience more personalized and effective.

- Engaging: Captures and maintains students’ interest and motivation.

- This often includes interactive elements, real-world applications, and opportunities for active participation, making learning enjoyable and stimulating.

- Accessible: Designed to be usable by all students, regardless of their abilities.

- This includes providing materials in multiple formats (e.g., text, audio, video), ensuring compatibility with assistive technologies, and using clear, simple language to make learning inclusive and equitable.

- Collaborative: Encourages students to work together, share ideas, and learn from one another.

- This often involves group projects, discussions, and peer feedback, fostering a sense of community and enhancing communication and teamwork skills.

- Hierarchical: Content organized in a clear, logical structure, making it easy for students to follow and understand.

- This includes a well-defined progression of topics to guide students through the material coherently and systematically.

Backwards Design

Backward course design identifies the desired learning outcomes, connects them to assessment tools, and aligns the curricular delivery and activities to assessments and learning outcomes.

In an inclusive design, goals must be relevant, assessments must be authentic, and content needs to be responsive.

Inclusive Practices

Inclusive practices aim to provide all students with a path to academic success regardless of background and ability. Strategies including Universal Design for Learning (UDL), flexible assessment, Inclusive Pedagogy, cultural competence, social support, and feedback mechanisms for course improvement provide faculty with options to create equitable and supportive classroom spaces.

Milestone (Learning Objectives) weekly, module, etc.

Creating a roadmap for a course involves aligning milestones with learning objectives to ensure a structured and effective learning experience. Here’s a brief outline:

| Step | Description |

|---|---|

| Identify Learning Objectives | Define what students should know or be able to do by the end of the course. |

| Break Down Objectives into Weekly or Modular Milestones | Divide the learning objectives into smaller, manageable milestones that can be achieved throughout the course. |

| Scaffold Milestones | Organize the milestones, taking a scaffolding approach and ensuring that each build on the previous ones. |

| Design/Align Assessments | Create assessments that align with each milestone to measure student progress and understanding. |

| Plan Instructional Activities | Develop activities and materials that help students achieve each milestone and prepare for assessments. |

Assessment Tools

Faculty can use a variety of assessment tools to evaluate students' knowledge. These tools can be broadly categorized into formative (ongoing) and summative (at the end) assessments, each serving different purposes in the learning process.

The difference between formative assessments and summative assessments

| Formative | Summative |

|---|---|

| Formative assessments are ongoing evaluations during the learning process aimed at providing feedback to improve student learning and adjust teaching methods. Examples include quizzes, class discussions, and exit tickets. | Summative assessments, on the other hand, occur at the end of a learning period and measure the overall achievement of learning outcomes. Examples include final exams, major projects, and standardized tests. |

Here are several commonly used tools:

| Tool | Description |

|---|---|

| Quizzes and Tests |

|

| Assignments and Projects |

|

| Presentations |

|

| Portfolios and Journals |

|

| Performance-Based Assessments |

|

| Formative Assessments |

|

| Discussion and Debates |

|

Example:

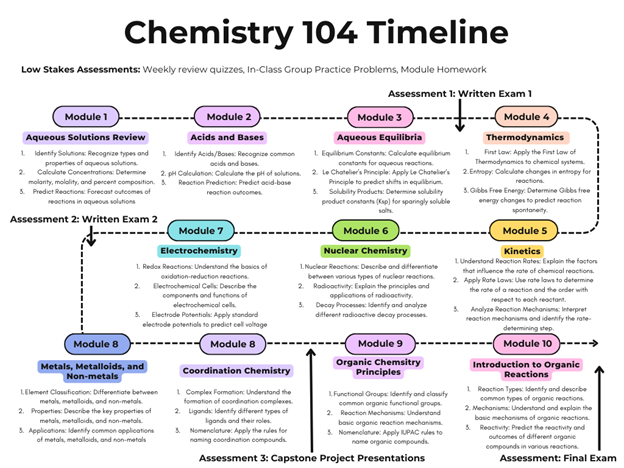

Note: This example was created to illustrate the idea of creating a roadmap or timeline. This timeline is not currently used by chemistry. Also, as courses evolve, continuously review your course structure and adjust based on student feedback and performance.

Varied, Frequent, and Low-Stakes Assessment Strategies

Varied, frequent, and low-stakes assessments can promote student success, inclusion, and equity in your classroom by:

| Area | Benefit |

|---|---|

| Student Success | Allowing for regular feedback and helping students identify areas for improvement early on. Lowering the pressure associated with high-stakes exams, reducing test anxiety, and improving students' performance. Catering to different learning styles, ensuring all students can demonstrate their understanding. |

| Equity and Inclusion | Ensuring that students with diverse needs and abilities can participate fully. Keeping students engaged by providing different ways to interact with the material. Creating a supportive learning environment where mistakes are seen as part of the learning process |

Strategies below help create a supportive and inclusive learning environment, allowing students to demonstrate their understanding in various ways and receive ongoing feedback to improve their performance.

| Strategy | Description |

|---|---|

| In-Class Activities | Interactive activities during class to apply concepts. Example: Group problem-solving tasks or case study discussions. |

| Frequent Quizzes | Short, regular quizzes to check understanding of recent material. Example: Weekly multiple-choice quizzes on key concepts. |

| Reflection Journals | Students write brief reflections on what they learned and how it applies to their lives. Example: Weekly journal/blog entries connecting course content to personal experiences. |

| Peer Reviews | Students review and provide feedback on each other’s work. Example: Peer review of essay drafts or project proposals. |

| Milestone Assignments | Breaking down larger projects into smaller, manageable tasks. Example: Submitting sections of a research paper (e.g., introduction, methods) at different points in the semester. |

| Online Discussion Forums | Platforms where students can discuss course topics and ask questions. Example: Weekly discussion posts responding to prompts related to the readings. |

| Low-Stakes Mastery Exams | Exams that students can retake to achieve mastery. Example: Online quizzes with multiple attempts allowed. |

| Scenario-Based Assessments | Assessments based on real-world scenarios. Example: Simulated business scenarios where students make decisions and analyze outcomes. |

Managing Grading for Low-Stakes Assignment

Efficient grading of frequent low-stakes assessments allows instructors to provide timely feedback, reduces student and instructor stress, and keep everyone engaged. It saves instructors time and helps identify learning gaps quickly, allowing for more tailored instruction.

Here are some strategies for streamlining grading of frequent low-stakes assessments:

| Strategy | Description |

|---|---|

| Automated Grading Tools | Use built-in tools in Canvas to automatically grade quizzes and assignments (i.e. survey quizzes). |

| Online Quizzes | Utilize multiple-choice, true/false, and short-answer questions that can be automatically graded. |

| Detailed Rubrics | Develop clear, detailed rubrics for assignments and provide rubrics to students beforehand so they understand the grading criteria. |

| Peer Review | Provide training resources for student sot understand the rubric and have students review and grade each other’s work based on a provided rubric. |

| Focus on One Aspect | Focus feedback on the most critical aspects of the assignment rather than commenting on every detail. Focus on aspects students will need for future assignments. |

| Comment Banks | Create a bank of common comments and feedback that can be quickly inserted into student work. |

| Group Assignments and Group Grading | Grade the group as a whole and provide contribution rubrics to consider individual contributions. |

| Flexible Deadlines | Stagger assignment deadlines to avoid having to grade all submissions at once. |

Connect with your students.

Faculty can strategically build lecture content that promotes connections with their students and builds a positive classroom climate. Here are some effective strategies:

| Strategy | Description |

|---|---|

| Lecture openers | Review questions, thought-provoking videos and songs, and news highlights can help students start to think critically about the content to be discussed in the lecture. Example: "Share one thing you remember from our last lecture (or from the readings, etc.)" |

| Open-Ended Questions | Add open-ended questions throughout your course materials (i.e., lecture slides) that invite multiple perspectives and do not have a single "correct" answer. Example: "What consequences do you think this policy will have on….? |

| Case Studies & Real-World Problems | Include case studies or current issues related to the course in your lectures. This promotes problem-solving discussions. Example: Follow up with reflective questions like, "What alternative approaches could have been considered?" |

| Leverage Technology | Use discussion boards, collaborative platforms (Google Docs, Padlet), or polling tools (like PollEverywhere, Mentimeter, Kahoot) to gather real-time input and promote interaction. Example: After group discussion, use Padlet to share ideas with other groups. |

| Create Active Learning Moments | Incorporate interactive activities like debates, role-playing, or simulations to help students connect through shared experiences. Example: Role-play a stakeholder meeting where each student takes on a different perspective. |

| Short Student-Led Discussions | Invite students to present or debrief on a topic or lead a discussion. You can rotate this responsibility so that all students have a chance to participate. Example: Students prepare questions based on assigned materials for discussion |

For large sections (over 100 students)

Think about how companies build a connection with each customer.

- Create a schedule to visit each discussion session.

- Schedule discussion session visits strategically throughout the semester, such as one section per week or a few sections after each major exam. Spending time with your students in a smaller section will allow them to ask you questions directly and build a personal connection with you.

- Split your classroom into areas. Consider using a gridline format to break your classroom into areas that you can intentionally interact with.

- Intentionally, focus on a few sections in each class. This will allow you to ensure that all students have an opportunity to participate.

- Split your classroom into groups and ask different groups to participate.

- Use different group activities to engage all students and have each group share their findings.

- Consider asking groups to rotate who is presenting their finding each session to increase student participation.

- Create a messaging system to communicate with different groups within your course.

- Consider dividing your course based on exam performance, department/major, class performance, etc.

- Email each group at different times in the semester and slowly connect with all students.

Email Example 1:

Subject: Invitation to Share Your Success Strategies

Dear [Student’s Name],

I hope this email finds you well. I wanted to take a moment to commend you on your outstanding performance in our [Course Name] class. Your dedication and hard work have not gone unnoticed, and I am truly impressed by your achievements.

Given your success, I would like to invite you to share the strategies and approaches that have been working well for you with me. Your insights could be incredibly valuable for your continued success and for helping your peers who might benefit from your experiences.

Would you be available to meet on [Proposed Date and Time]? If this time does not work for you, please let me know your availability, and we can arrange a suitable time.

Thank you for your continued effort and excellence in the course. I look forward to our discussion.

Best regards,

[Your Name]

[Your Title]

[Your Contact Information]

Email Example 2

Subject: Let’s Work Together to Improve Your Experience in [Course Name]

Dear [Student’s Name],

I hope this message finds you well. I wanted to reach out because I’ve noticed you’ve been facing some challenges in our [Course Name] class. Your success in this course is very important to me, and I would like to offer my support to help you overcome these difficulties.

I would love to meet with you to discuss your experience in the course so far. Understanding the obstacles you’re encountering will help me provide you with the necessary support and improve the course for everyone. Your feedback is invaluable; together, we can identify strategies that might work better for you.

Would you be available to meet on [Proposed Date and Time]? If this time doesn’t suit you, please let me know your availability, and we can arrange a more convenient time.

Thank you for your hard work and perseverance. I am here to support you and am committed to helping you succeed.

Best regards,

[Your Name]

[Your Title]

[Your Contact Information]

- Involve your TAs or CAs in helping you identify students to connect with.

- If you want to connect with underperforming or “at-risk” students, ask your instructional team members weekly or bi-weekly to give you a list of students who might benefit from an email from you. Consider using criteria like:

- Attendance

- Participation

- Signs of distress

- You can use this opportunity to connect them with course and campus resources and directly invite them to use your office hours.

- If you want to connect with underperforming or “at-risk” students, ask your instructional team members weekly or bi-weekly to give you a list of students who might benefit from an email from you. Consider using criteria like: