UDL Tip of the Month 2025

UDL and Instructor Reflection: Designing for Continuous Improvement

By Marc Thompson (CITL)

One of the great paradoxes of asynchronous online courses is that the design itself becomes a source of instruction, yet the instructor is rarely present to witness those revelatory moments of learner confusion, frustration, or insight. In this environment, barriers are often invisible until they reveal themselves in the form of poor performance, late submissions, or excessive help-seeking emails. To address this challenge, university instructors can benefit from adopting a Universal Design for Learning (UDL) mindset that views each course offering as a valuable opportunity to design for, and capture, learner insights for optimizing students' learning experiences.

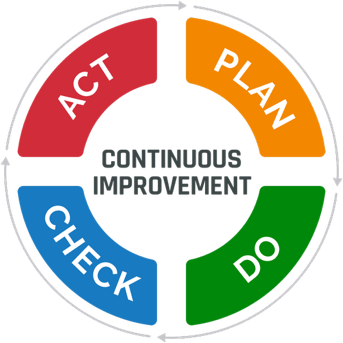

Implementing UDL requires continuous and evolving design, and instructor reflection is crucial to this active cycle of refinement. The Plan, Do, Check, and Act (PDCA) cycle, a framework widely used in management for Continuous Quality Improvement (CQI), provides one method for approaching the reflection and improvement process in applying UDL principles. This iterative process aligns with the UDL +1 approach to incremental change (Tobin & Behling, 2018), as well as formal quality standards, such as the Quality Matters (QM) rubric (Robinson & Wizer (2016).

Phases 1 & 2: Planning and Designing for Discovery (Plan & Do)

So let's get down to the nuts and bolts of it all. The first critical step in leveraging a cycle of continuous improvement is to leverage the course design to proactively collect diagnostic feedback from learners. In addition to more generic end-of-course surveys, instructors can creatively embed specific, low-stakes activities (the Do phase) that invite specific learner feedback and inform the Plan for future revisions.

- For Engagement and Relevance: A social sciences instructor teaching a Policy course might offer a non-graded, two-question "Relevance Check" Quiz after a required reading, asking students to rate how well topics connect to their career goals.

- For Representation Clarity: An instructor teaching a literature course can establish an anonymous, permanent "Muddiest Point" Discussion Board (IRIS Center). The instructor then tracks the volume and content of these anonymous posts. High volume of muddiest posts on a specific module reveals a design friction point, confusing instructions or dense text perhaps, that might be improved with revision. This proactive auditing aligns with quality assurance standards for online learning (Quality Matters, 2021).

- For Sustaining Effort (Engagement): A Chemistry Lab instructor requires students to complete a brief, zero-point "Effort Tracker" Survey after the first complex lab write-up, asking for the estimated time spent and self-rating on confidence in the data analysis.

- For Planning and Strategy (Action & Expression): When offering flexible final project options, a Business instructor can set up a mandatory, one-point "Assignment Checkpoint" early on, requiring a 1-2 sentence project proposal stating the topic and intended submission format (e.g., video presentation, written plan, infographic, etc.).

Phase 3: Informed Reflection (Check)

Once learner insights are gathered from these embedded diagnostic tools, the instructor moves into the Check phase to reflect on barriers and points of friction and uncover the underlying UDL principle that was not fully supported.

- Representation Barrier (Clarity): If an analysis of Canvas usage shows an unusually high bounce rate on a specific required reading page, it may reflect a Representation barrier because the content is too dense, needs further chunking and organization, or lacks visual aids (Burgstahler, 2015).

- Engagement Issue (Relevance): If the Relevance Check Quiz indicated low scores for a specific course module, this suggests the instructor might want to consider ways of strengthening the connection between that module's content and students’ personal or professional interests.

- Representation Issue (Organization/Cognitive Load): If the Chemistry Effort Tracker shows an average time spent that is double the expected workload and low confidence scores, the diagnosis is a failure in Representation—the instructions were likely too dense, lacked visual organization, or the grading rubric was unclear.

- Action & Expression Failure (Executive Functions): If a significant number of students fail to complete the mandatory Business Project Checkpoint, it suggests a barrier in Action & Expression; the instructor failed to provide sufficient scaffolding or support for early planning and strategy development.

- Action & Expression (Demonstrating Knowledge): When an instructor in a STEM course offers flexible final project options, they can set up a zero-point assignment early on, asking students to state their intended project format. If 95% of students choose the written technical report, the instructor may want to reflect on the design of the other options. For example, did one or more of the options lack sufficient scaffolding, or a clear example, to be perceived as a viable choice?

Phase 4: Creative Refinement (Act)

Finally, instructor reflection drives the Act phase, the last step of revision which closes a given cycle in the continuous improvement loop. In this phase, actions taken are small, intentional, and based on evidence collected through proactive course design.

- Refining Representation through Chunking: If the instructor detected a problem with language density in a lab document, the revision may go beyond adding an explanatory footnote and perhaps involve chunking the long lab instructions into three separate course pages: Pre-Lab Tasks (Checklist), Data Collection Protocol (Step-by-step), and Post-Lab Analysis & Write-up (Grading criteria). This deeper structural revision improves the representation of course material and reduces cognitive load.

- Refining Engagement through Relevance: If students are avoiding an optional "Current Events Connection" discussion board, revision might involve changing the activity's purpose, making it a mandatory, low-stakes requirement where students find one real-world example that their main assignment for that unit or module must reference. This type of revision strengthens engagement by increasing the authenticity and value of the task for learners.

- Refining Action & Expression Scaffolding: If a STEM instructor confirmed that learners were avoiding the recorded presentation option, constructive revision might involve creating a sample template or "how-to" video demonstrating the recording process. This type of revision could help by providing necessary scaffolding that makes the assignment choice clearer (CAST, 2018).

- Refining Action & Expression Strategy Support: To address the skipped Project Checkpoint, the instructor provides a scaffolded template that students simply fill out with Topic, Goal, and Output Method. This minimal requirement provides executive function support by requiring students to plan early.

UDL-informed self-reflection has the potential to transform an instructor from content deliverer to responsive course design architect. By proactively embedding feedback mechanisms into the course, such as relevance checks and effort trackers, the instructor can gather helpful diagnostic evidence for identifying and removing learning barriers. This UDL-guided responsive course design is what allows the course to evolve continuously, offering new, more equitable and robust learning pathways.

Ultimately, continuous improvement of applied UDL involves active reflection coupled with responsive course design. Focusing on small, high-impact revisions based on evidence collected from learners can ensure that courses are not only more accessible but intentionally designed for the success of the diverse learners they serve.

References

- Burgstahler, S. E. (2015). Universal design in higher education: From principles to practice. In S. E. Burgstahler (Ed.), Universal design in higher education: From principles to practice (2nd ed., pp. 317–328). Harvard Education Press.

- CAST. (2018). Universal design for learning guidelines version 2.2. Retrieved from http://udlguidelines.cast.org

- IRIS Center. (n.d.). Universal design for learning (part 2): A closer look at the principles. Peabody College, Vanderbilt University. Retrieved from https://iris.peabody.vanderbilt.edu/module/udl/

- Quality Matters. (2021). Quality matters higher education rubric (7th ed.). Quality Matters.

- Robinson, D. E., & Wizer, D. R. (2016). Universal Design for Learning and the Quality Matters Guidelines for the Design and Implementation of Online Learning Events. International Journal of Technology in Teaching and Learning, 12(1), 17–32.

- Tobin, T. J., & Behling, K. (2018). Reach everyone, teach everyone: Universal design for learning in higher education. West Virginia University Press.

Designing Workshops for Everyone: A UDL Approach

by Marc Thompson (CITL)

This month's Tip of the Month article considers UDL from a professional development perspective; specifically, how we can apply Universal Design for Learning (UDL) to design and deliver workshops that engage everyone, whether they’re new faculty, seasoned staff, or graduate instructors. UDL can help us anticipate participant variability and offer flexible ways to engage, understand, and respond, making our workshops more inclusive and impactful for everyone involved.

Here are a few practical strategies for applying UDL in the design, delivery, and post-delivery of your workshops.

Before the Workshop: Design with Flexibility in Mind

- Set Clear, Meaningful Goals. Define one or two SMART goals (Specific, Measurable, Achievable, Relevant, Time-bound). Share them at the start so participants know what they’ll gain from the session (Thompson, 2024b).

- Anticipate Learner Variability. Consider who will attend and what prior experience, needs, or barriers they may bring. Plan content that works across preferences: visual, auditory, textual, and interactive (Yacapsin, 2024).

- Use Varied Materials. Gather content in multiple formats (slides, short readings, videos with captions, infographics, or audio clips). Share materials ahead of time, ensuring digital accessibility (e.g., readable PDFs, alt text, captions (Thompson, 2023b).

- Plan for Engagement. Build activities that spark interest and relevance. Include a mix of reflection, small-group, and large-group work, and connect topics to participants’ real-world challenges or goals (Thompson, 2023a).

- Build in Flexibility (+ 1 Method). Always add one more way to access or participate (Thompson, 2025c).

- Decide How Participants will Demonstrate Learning. Plan one or two flexible ways for participants to show what they’ve learned, such as a brief written reflection, a poll response, or pair-share summary (Thompson, 2024a).

During the Workshop: Deliver with Multiple Means in Mind

- Start with an Anchor Activity. Begin with a brief poll, prompt, or icebreaker that connects the topic to participants’ experiences. The aim here is to clearly communicate your goals and provide an overview of what’s ahead (Thompson, 2023a).

- Present Content in Multiple Ways. Combine visuals, narration, and text summaries. Take time to pause and highlight key terms and concepts (Thompson, 2023b).

- Facilitate Active, Flexible Participation. Mix large-group discussion, breakout groups, and individual reflection. Encourage both verbal and written contributions.

- Check for Understanding Frequently. Use quick tools like a thumbs-up/down, short polls, or “type one takeaway” prompts. Adjust pacing or explanation based on responses (Thompson, 2024c).

- Wrap up with Flexible Reflection. Summarize key takeaways aloud and on a slide or shared document. Invite participants to choose how to reflect (Thompson, 2025b).

After the Workshop: Extend Learning Accessibly

- Send a Quick Follow-up. Share a short summary or key resources by email or shared folder. Include both text and links to visuals or recordings (with captions).

- Invite Feedback in Multiple Ways. Provide several feedback options: e.g., survey, shared doc, or short voice memo (Thompson, 2025a).

- Reflect on What Worked. Ask yourself: Did the design anticipate different participation styles (Thompson, 2025c)?

Quick Reference: Three UDL Principles in Workshop Design (CAST, 2020)

| UDL Principle | Focus | Workshop Strategies |

|---|---|---|

| Engagement (The Why) | Motivate interest, relevance, and sustained participation. | Build Community and Choice: Offer flexible pathways for contribution (verbal/written) and connect content to learners' goals using real-world scenarios and optional reflection. |

| Representation (The What) | Present content in diverse, accessible formats. | Offer Varied Formats and Scaffolding: Present information using a blend of audio, visuals, and text, and provide advance materials (glossaries, captioned videos) to support comprehension. |

| Action & Expression (The How) | Provide flexible ways for participants to respond or demonstrate learning. | Enable Flexible Demonstration: Provide choices for showing mastery, such as written reflection, visual output (screenshot annotation), or verbal summaries, using collaborative and low-tech tools. |

Final Thoughts

You don’t need to overhaul your entire workshop to make it more inclusive. Start with one +1 addition, one extra option, one alternative format, one new way to engage. Those small changes compound over time, creating learning spaces that model the same inclusive, flexible practices we aim for in every classroom and online course.

References

- CAST (2020). UDL Tips for Designing Learning Experiences. Wakefield, MA: Author. Retrieved from https://www.cast.org/resources/tips-articles/udl-tips-designing-learning-experiences/

- Thompson, M. (2025c, August). "The power of one: Using the Plus-One UDL approach". Center for Innovation in Teaching & Learning, University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign. https://citl.illinois.edu/udl-tip-month-2025

- Yacapsin, M. (2024, October). "Addressing learner variability in your classroom". Center for Innovation in Teaching & Learning, University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign. https://citl.illinois.edu/udl-tip-month-2024

- Thompson, M. (2024c, December). "Building bridges: UDL and instructional scaffolding". Center for Innovation in Teaching & Learning, University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign. https://citl.illinois.edu/udl-tip-month-2024

- Thompson, M. (2024b, November). "Clear goals, multiple means". Center for Innovation in Teaching & Learning, University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign. https://citl.illinois.edu/udl-tip-month-2024

- Thompson, M. (2025a, February). "Wise feedback and UDL strategies for promoting learner agency". Center for Innovation in Teaching & Learning, University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign. https://citl.illinois.edu/udl-tip-month-2025

- Thompson, M. (2025b, May). "Neurodiversity and UDL: Strategies for supporting all brains". Center for Innovation in Teaching & Learning, University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign. https://citl.illinois.edu/udl-tip-month-2025

- Thompson, M. (2024a, January). "Multiple means of action and expression". Center for Innovation in Teaching & Learning, University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign. https://citl.illinois.edu/udl-tip-month-2024

- Thompson, M. (2023b, December). "Multiple means of representation". Center for Innovation in Teaching & Learning, University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign. https://citl.illinois.edu/udl-tip-month-2023

- Thompson, M. (2023a, November). "Multiple means of engagement". Center for Innovation in Teaching & Learning, University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign. https://citl.illinois.edu/udl-tip-month-2023

UDL vs. Accessibility: What's the Difference and How Do They Work Together?

By Marc Thompson (CITL)

In the context of teaching and learning, "accessibility" and "Universal Design for Learning (UDL)" have become key concepts for creating effective and inclusive learning environments. While often used in the same conversation, these two frameworks have distinct goals and applications. Understanding their unique roles and how they intersect is essential for educators, instructional designers, and eLearning professionals.

What is Accessibility?

Accessibility is a targeted approach focused on removing specific barriers for individuals with disabilities. It's often driven by compliance with legal standards, like the recent Title II Update to the Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA), which mandate equal access to information and resources. In higher education, this translates to concrete actions such as ensuring PDFs are properly tagged for screen readers used by students with visual impairments or providing accurate captioning for video content. In the teaching and learning space, accessibility is about ensuring that digital programs, services, and activities meet specific guidelines so that all users can perceive, operate, and understand the content.

What is Universal Design for Learning (UDL)?

UDL, on the other hand, is a proactive framework for designing flexible and inclusive learning environments from the outset. It is built on the premise that learners are diverse and a "one-size-fits-all" approach will always create barriers. UDL's three core principles (Multiple Means of Representation, Multiple Means of Action & Expression, and Multiple Means of Engagement) guide the creation of flexible learning paths. For instance, a UDL-informed course might offer a digitally accessible textbook, a podcast with accurate captions, and an infographic with appropriate alternative text description. This design choice benefits all learners by allowing them to choose the format that best suits their learning needs, while also providing an accessible option for those who require it.

UDL's scope often extends beyond accessibility. For example, offering students a choice between a written essay and an oral presentation to demonstrate their knowledge is a UDL strategy (Multiple Means of Action & Expression) that accommodates different learning strengths and preferences, without being a specific accessibility requirement. Similarly, allowing students to choose their own research topic within a broader course theme is a UDL strategy (Multiple Means of Engagement) that helps motivate learners by connecting the material to their personal interests, but it is not a measure required for accessibility.

Where do Accessibility and UDL Intersect?

The overlap between these frameworks is significant, particularly in the UDL principle of Multiple Means of Representation. Many accessibility measures directly support this principle. For example, providing a text transcript for a video is an accessibility requirement for deaf and hard-of-hearing students. However, this same transcript also serves as an additional mode of representation for any student who prefers to read the content, or who needs to quickly search for specific information within the lecture. Similarly, creating properly structured headings in a digital document benefits students using screen readers (accessibility) and also helps all students better navigate and understand the document's organization (UDL). This convergence of purpose is what makes them more like "compatible partners" and not a "conflicted marriage" (Educause Review).

Creating Synergy between Accessibility and UDL

While they are distinct, neither framework is superior to the other. Accessibility sets the foundational requirements for an inclusive learning environment, while UDL builds on this foundation to create a more dynamic, flexible, and engaging experience for a broader range of learners. The most effective educational design strategy integrates both, as this approach "removes barriers and creates true opportunities for choice" (Johns Hopkins CTL).

Here are a few examples of how this potential synergy might work:

- Course Readings: To meet accessibility standards, all digital PDF readings should be screen-reader accessible. A UDL strategy would then offer these readings in multiple formats, such as an HTML version of the article or an audio file with an accompanying text transcript. This provides options for students who may have reading challenges or who prefer to listen to content.

- Assignments: An accessible assignment prompt would be clearly written and formatted with proper headings. The UDL approach might then expand on this by offering multiple ways for students to complete the assignment. For a research project, instead of a single traditional paper option, students could also be given the option to create a podcast with transcript, short captioned documentary, or infographic series with appropriate use of alt text. This meets accessibility needs while at the same time allowing students with different strengths and abilities to demonstrate their knowledge effectively.

- Data Visualization and Graphics: For charts, graphs, or infographics, an accessibility requirement is to provide alt-text (alternative text description) or a full written description so that a screen reader can interpret the visual data for a student with a visual impairment. A UDL strategy could complement this by providing a downloadable spreadsheet of the raw data. This not only gives the student with a visual impairment an additional way to process the information, but it also allows any student to manipulate the data themselves for deeper analysis or to use it in their own projects.

- Digital Tools and Software: When adopting new educational technology, accessibility dictates that the platform itself must be usable with assistive technology, and the content within it must also be accessible. From that vantage point, a UDL strategy could then leverage the platform's features to provide students with additional choice and customization options. For instance, a course management system might allow students to personalize their dashboard to view upcoming assignments in a list, calendar, or grid format based on their preference, all while ensuring the underlying content is accessible to a screen reader.

Ultimately, "digital accessibility is an essential part of UDL" (Bureau of Internet Accessibility). By first ensuring that all course materials are accessible, and then applying UDL principles to offer flexible learning options, we can create truly inclusive courses where every student has the opportunity to succeed.

References

- Ableser, J., & Moore, C. (2018, September 10). Universal Design for Learning and Digital Accessibility: Compatible Partners or a Conflicted Marriage? EDUCAUSE Review. https://er.educause.edu/articles/2018/9/universal-design-for-learning-and-digital-accessibility-compatible-partners-or-a-conflicted-marriage. Retrieved September 17, 2025.

- Greene, C. (2022, June 3). Digital accessibility’s intersection with Universal Design for Learning. Center for Teaching and Learning Blog, Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health. https://ctl.jhsph.edu/blog/posts/accessibility-intersection-with-UDL/. Retrieved September 17, 2025.

- Bureau of Internet Accessibility. (2022, November 29). Understanding the overlap between UDL and digital accessibility. BOIA Blog. https://www.boia.org/blog/understanding-the-overlap-between-udl-and-digital-accessibility. Retrieved September 17, 2025.

The Power of One: Using the Plus-One UDL Approach

By Marc Thompson (CITL)

If you have ever felt overwhelmed by the thought of using the Universal Design for Learning (UDL) framework to redesign your entire course, you’re not alone. Many instructors share that feeling, and this is exactly why the “Plus-One” approach, popularized by author and educator Thomas Tobin, is so effective. 1

The Plus-One approach is simple: instead of trying to implement every UDL guideline at once, make just one small, intentional addition to your course. Then, observe how it works, reflect on its impact, and decide whether to keep it, adjust it, or set it aside before adding the next “plus one.” This iterative process makes UDL less of a daunting course overhaul and more of a manageable, ongoing practice that steadily and reflectively builds a more inclusive course design.

Where to Start?

While the syllabus is a great place to begin, there are many other high-impact, low-effort places to apply the Plus-One approach (for more on the syllabus, see our three-part series on UDL-ifying Your Syllabus) 2, 3, 4. The key is to look for a single, manageable barrier in your course and add one option to address it. Need some inspiration? Here are a few examples to get you started.

Some Plus-One Examples

- Writing-intensive courses: Alongside traditional essays, give students the option to submit a podcast episode or blog-style reflection. This allows them to practice the same critical thinking and argumentation skills in different formats.

- STEM labs: For complex procedures, create a short checklist or flowchart that summarizes key steps in addition to the full lab manual. This supports students who benefit from visual or simplified guides.

- Public Health or Social Sciences courses: When introducing a new data set, offer a pre-made visualization or summary in addition to the raw data table. This helps students with different data literacy levels grasp the key trends and patterns before diving into their own analysis.

- Foreign language courses: If you primarily assess speaking skills through in-class presentations, add the option for students to submit an audio or video recording. by offering additional means of action and expression, this can reduce anxiety for some learners and provide more time for thoughtful articulation.

- Business or Communication courses: When assigning a persuasive paper, offer students the additional choices to create a multimedia presentation or a detailed infographic instead. This addition promotes learning by providing multiple means of action and expression for students to work with a format that aligns with their strengths and interests.

- Computer Science or Engineering courses: If you notice some students struggle with live coding demos, provide the completed code file as a download after class. This allows them to focus on your explanation during the demonstration rather than trying to type and keep up, offering another means of representation.

- History or Literature courses: Add a podcast, documentary clip, or interactive timeline alongside a text-heavy reading. A single alternative can improve learning by providing multiple means of representation.

- Graduate seminars: Offer students the option to submit discussion questions in advance through a shared document. This encourages deeper preparation and ensures quieter students’ perspectives are included.

- Online or hybrid courses: Add a short “week overview” video highlighting objectives and key tasks, in addition to the text-based course module. This supports students who benefit from hearing the content and seeing it emphasized.

- For any course with a discussion component: If you notice some students are hesitant to speak up in class, add one option for them to participate. This could be setting up a backchannel chat on a collaborative document or an online forum where they can post questions or comments during or after the lecture. This encourages multiple means of engagement and provides a voice for quieter learners.

The Process: Implement, Reflect, Evolve

Implementing your “plus one” is just the start. The real value comes from reflection and continuous improvement. Did students use the new option you added? Did it improve understanding or engagement? Informal feedback through a quick poll, short survey, or simply observing student interactions, can help you gauge effectiveness.

For example, if you added a video option for a lab report, review what students submitted. Did the videos show strong understanding? If so, consider keeping or expanding the option. If not, ask students for feedback: Was the format unclear? Did the assignment need more structure? Adjust, refine, or replace as needed. Ultimately, the Plus-One approach is not about perfection; it's about progress. By taking small, deliberate steps and continuously reflecting on their impact, you can steadily build a course that is more inclusive, engaging, and effective for all.

References

- Tobin, T. J., & Behling, K. T. (2018). Reach everyone, teach everyone: Universal design for learning in higher education. West Virginia University Press.

- CITL. (2024, April). UDL-ify Your Syllabus: Engagement. University of Illinois.

- CITL. (2023, May). UDL-ify Your Syllabus: Representation. University of Illinois.

- CITL. (2024, June). UDL-ify Your Syllabus: Action and Expression. University of Illinois.

Image Credit: Google Plus One Icon, via Very Icon. Retrieved 8-22-2025.

Neurodiversity and UDL: Strategies for Supporting All Brains

By Marc Thompson (CITL)

University classrooms are diverse—not just in terms of students’ backgrounds and experiences, but also in the ways their brains take in, process, and express information. Neurodiversity is the idea that neurological differences like ADHD, autism, dyslexia, anxiety, and other cognitive variations are natural parts of human diversity. Instead of viewing these as deficits, the neurodiversity paradigm encourages educators to recognize and value different ways of thinking and learning.1

Universal Design for Learning (UDL) offers a proactive framework to foster inclusion by addressing learner variability from the start. This month’s UDL tip explores some ways to support neurodiverse learners through practical, discipline-specific strategies anchored in UDL principles. Here are five “Quick Win” UDL strategies to better support neurodiverse students, along with examples from a range of discipline areas.2

Quick Win 1: Offer Multiple Ways to Access Course Content

UDL Principle: Provide Multiple Means of Representation

Learners differ in how they perceive and process information. All learners, including neurodiverse learners, benefit when information is available in more than one format. This method of providing multiple ways to access course content supports varied cognitive processing styles and sensory preferences. For example, students with dyslexia may benefit from audio or visual materials, while students with autism may appreciate consistent formats and clear, written expectations in addition to spoken instructions.3

UDL Strategies (Quick Win 1)

- Provide lecture materials in multiple formats—such as slide decks with speaker notes, transcripts for videos, or a text-based outline alongside recorded lectures.

- Use visual supports such as flowcharts, infographics, and labeled diagrams to illustrate complex concepts.

- For auditory learners or those who process language differently, consider offering narrated screencasts or podcast-style summaries.

Examples (Quick Win 1)

- Chemistry: Supplement complex diagrams with narrated walkthroughs and plain-language explanations. Accompany written lab instructions with a short video demonstration and a printable checklist of steps.

- Literature: Offer audio versions of texts alongside print and digital copies. Offer audiobook versions of assigned novels along with annotated digital texts.

- Philosophy: Use visual concept maps to break down abstract ideas and show relationships between arguments.

- History: Provide transcripts alongside video lectures on the causes of the Cold War. Provide both a timeline graphic and a narrative summary of historical events, allowing students to understand chronological sequences in multiple ways.

- Mathematics: Provide a worked example and a video explanation in addition to formula sheets.

- Physics: Share a visual simulation of a pendulum’s motion in addition to written, and any related mathematical, description.

- Business: Supplement textbook chapters on marketing strategy with infographics and short podcasts.

Quick Win 2: Offer Choices to Increase Autonomy

UDL Principle: Provide Multiple Means of Action and Expression

Not all students express what they know in the same way. UDL encourages offering options for how learners demonstrate their knowledge and helping them plan and organize their work. These options can be especially helpful for allowing neurodiverse learners to leverage their strengths, while also reducing stress and increasing motivation.4

UDL Strategies (Quick Win 2)

- Offer multiple deliverable options for assignments, such as a paper, a slide deck with audio narration, a video explanation, or a creative project like a podcast or infographic.

- Allow alternatives to timed tests when appropriate, such as take-home exams or open-book assessments with time flexibility.

- Use frequent, low-stakes formative assessments to build confidence and reduce pressure.

Examples (Quick Win 2)

- Political Science: Let students choose between writing a policy brief, recording a video op-ed, or creating an infographic for a local issue.

- Statistics: Break large assignments into smaller steps with scaffolded deadlines and optional peer feedback.

- World Language Instruction: Allow oral exams, written reflections, or multimedia storytelling projects.

- Education: Use rubrics that assess learning objectives across multiple formats (e.g., lesson plans, recorded microteaching, reflective journals).

- Engineering: Provide templates or organizational tools to support project planning and time management. Allow teams to present project findings via a slide deck, poster, or prototype demo.

- Sociology: Let students choose between writing a paper, recording a video presentation, or designing an infographic to analyze a social issue.

- Psychology: Students may write a case study analysis or record an audio reflection with supporting evidence.

- Art History: Permit written analysis or a narrated virtual gallery tour comparing art movements.

- Public Health: Accept either a policy brief or a podcast-style interview with an expert on health disparities.

Quick Win 3: Develop Predictable, Supportive Course Structures

UDL Principle: Provide Multiple Means of Engagement

Ambiguity and unstructured tasks can increase cognitive load or anxiety. Some neurodiverse students also struggle with organizing ideas, managing time, or initiating tasks. At the same time, many neurodiverse students thrive in predictable environments with clear routines and expectations along with supportive tools that improve the learning experience for all students.5

UDL Strategies (Quick Win 3)

- Use consistent weekly module formats in your LMS with clearly labeled sections: Overview, Objectives, Readings, Activities, and Assignments.

- Include a checklist or visual roadmap at the start of each module to show what’s expected.

- Be explicit about grading criteria with rubrics and examples of successful work.

Examples (Quick Win 3)

- Philosophy: Post a weekly roadmap with due dates, reading summaries, and guiding questions.

- Education: Use headings and icons consistently to distinguish activities, discussions, and assignments.

- Mathematics: Create brief tutorial videos, each focused on one type of equation or theorem.

- Chemistry: Break down lab reports into clear sections with templates (e.g., Objectives, Procedure, Results).

Quick Win 4: Reduce Cognitive and Sensory Load

UDL Principle: Provide Multiple Means of Engagement and Representation

Neurodiverse students—especially those with ADHD, autism, or anxiety—may experience heightened sensitivity to sensory input or difficulty filtering distractions. Others may become overwhelmed by complex layouts, dense text, or tasks that require multitasking without clear guidance. Simplifying course content layout, reducing visual noise, and breaking complex assignments into manageable steps can ease these burdens. These strategies don’t “water down” content—they help all learners access and interact with the same rigorous material through a clearer, more focused lens. In fact, all students benefit when the learning environment supports focus, clarity, and intentional pacing.6

UDL Strategies (Quick Win 4)

- Use clean, uncluttered slide designs and course pages with clear headings and minimal distractions.

- Break large assignments into smaller, scaffolded parts with individual due dates.

- Provide quiet options for collaborative activities, like asynchronous discussion boards or written group reflections.

- Avoid unnecessary animations or transitions that may distract from the main course content, unless they support the learning goal(s).

- Include estimated time commitments for activities to help with planning and time management.

Examples (Quick Win 4)

- Art: Instead of a loud, fast-paced critique session, students can upload work to a shared board and leave audio or written feedback for peers over a 48-hour window.

- Computer Science: Provide long-term projects with milestone check-ins and template documents to reduce decision fatigue and cognitive overload.

- Anthropology: Use collapsible sections in the LMS to group readings by theme and week.

- Linguistics: Present recordings and transcriptions in a side-by-side format to avoid toggling.

- Physics: Create a simplified version of data sets to focus students on specific trends before introducing full complexity.

Quick Win 5: Provide Scaffolds for Planning and Organization

UDL Principle: Provide Multiple Means of Action and Expression

Some neurodiverse students struggle with organizing ideas, managing time, or initiating tasks. Support tools can level the playing field. Executive functioning—skills involved in planning, organizing, prioritizing, and managing time—can be particularly challenging for neurodiverse students, especially those with ADHD or autism. These students often understand content well but sometimes struggle to initiate tasks or complete them in a structured, timely manner. UDL encourages educators to build in tools and prompts that support learners in managing their learning process. Scaffolds for planning and organization don’t give an unfair advantage—they remove unnecessary barriers and help all students become more self-directed, confident learners.7

UDL Strategies (Quick Win 5)

- Provide templates, outlines, or graphic organizers to help students get started on assignments.

- Offer planning checklists or timelines for major projects.

- Use progress trackers or milestone deadlines to guide multi-week tasks.

- Embed planning prompts within assignments (e.g., “What is your first step? What support might you need?”).

- Offer optional planning consultations or peer-planning sessions in person or online.

Examples (Quick Win 5)

- Nursing: Offer a clinical reflection template to guide analysis of patient interactions.

- Computer Science: Use flowcharts and pseudocode as pre-coding activities.

- Political Science: Provide timelines or mind-mapping tools to help plan policy analysis papers.

- Environmental Studies: Share a checklist for components of a fieldwork report.

- Theater: Offer a rehearsal planner template to track lines, cues, and personal notes.

Conclusion

At the end of the day, supporting neurodiverse learners isn’t about adding extra work—it’s about designing learning environments that recognize and celebrate the many ways students think, process, and express themselves. By incorporating even a few of these UDL-inspired strategies, you can create a more inclusive classroom that empowers all students to succeed, not in spite of their differences, but because of them. Small changes really do add up—and when we plan with learner variability in mind, everyone benefits.8

References

- Dwyer P. (2022). The Neurodiversity Approach(es): What Are They and What Do They Mean for Researchers? Human development, 66(2), 73–92. https://doi.org/10.1159/000523723

- CITL. (2024, September). Embracing Learner Variability. University of Illinois.

- CITL. (2023, December). UDL Principle 2: Multiple Means of Representation. University of Illinois.

- CITL. (2024, January). UDL Principle 3: Multiple Means of Action and Expression. University of Illinois.

- CITL. (2024, November). Clear Goals, Multiple Means". University of Illinois.

- CITL. (2024, February). 3 Strategies for Removing Threats and Barriers. University of Illinois.

- CITL. (2024, December). Building Bridges: UDL and Instructional Scaffolding. University of Illinois.

- CITL. (2024, March). Fostering Expert Learners. University of Illinois.

Image Credit: MissLunaRose12, CC BY-SA 4.0, via Wikimedia Commons. Retrieved 4-23-2025.

Engaging the Disengaged: UDL Strategies for Motivation and Persistence

By Marc Thompson (CITL)

Student disengagement is one of the biggest challenges in higher education. Whether due to external responsibilities, lack of confidence, or feeling disconnected from the course, some students struggle to stay motivated and persist in their learning. Universal Design for Learning (UDL) offers a flexible framework for meeting the diverse needs of learners by providing multiple ways to engage, represent, and express learning. By incorporating UDL principles, educators can create learning environments that foster motivation, enhance persistence, and support all students in staying engaged. This tip-of-the-month article explores several “Quick Win” UDL strategies aimed at re-engaging students through practical, discipline-specific approaches.

Quick Win 1: Make Learning Relevant and Purposeful

UDL encourages educators to present content in ways that are meaningful and relevant to diverse learners. When students see how the material connects to their personal interests or future goals, they are more motivated to engage.1 Offering multiple ways for students to relate course content to their own experiences, such as choice-based assignments and problem-based learning, empowers them to take ownership of their learning. These practices not only support engagement but also provide students with autonomy, a key principle of UDL.

- STEM Example: In a physics course, instead of using abstract equations alone, ask students to analyze the physics behind real-world scenarios like roller coasters, sports movements, or medical imaging technologies.

- Social Sciences Example: In a psychology course, students could choose a mental health topic that impacts their community and analyze it using course concepts, making the material more personally relevant.

- Business Example: Instead of having all students analyze the same case study, allow them to select a business or industry they are interested in and apply financial or marketing principles to it.

- Engineering Example: In an electrical engineering course, allow students to design a simple device that solves a real-world problem in their community, integrating both theory and practical application.

- Art Example: In an art history course, have students explore local art galleries or digital archives and analyze specific pieces that resonate with their personal experiences or backgrounds.

For more on Engagement, see the following CITL UDL Tip of the Month articles:

- CITL. (2023, November). Multiple means of engagement. University of Illinois.

- CITL. (2024, April). UDL-ify your syllabus: Engagement. University of Illinois.

Quick Win 2: Offer Choices to Increase Autonomy

A fundamental aspect of UDL is providing learners with choices—whether it’s in how they engage with content or how they demonstrate their understanding. Providing multiple means of action and expression gives students the freedom to choose assignments and activities that align with their strengths, interests, and learning preferences.2 This autonomy boosts motivation, as students feel more in control of their learning process. Even small choices—like letting students pick between two reading selections—can significantly enhance motivation and persistence.

- Humanities Example: In a history course, instead of requiring a traditional essay, allow students to demonstrate their understanding by creating a podcast episode, an infographic timeline, or a short video analysis

- STEM Example: In a biology class, students learning about ecosystems could choose between writing a research paper, designing an educational poster, or coding a simple simulation to demonstrate ecosystem interactions.

- Education Example: In a teacher preparation course, future educators could choose between writing a lesson plan, presenting a microteaching session, or developing a resource guide for fellow teachers.

- Law Example: In a law course, let students select a landmark case and either write a traditional analysis or create a visual case map to explain the case's impact on legal precedent.

- Philosophy Example: In a philosophy class, students could either write a reflective essay on a philosophical debate or engage in a recorded discussion where they present their arguments to peers.

For more on Multiple Means of Action and Expression, see the following CITL UDL Tip of the Month articles:

- CITL. (2024, January). Multiple means of action and expression. University of Illinois.

- CITL. (2024, June). UDL-ify your syllabus: Action and expression. University of Illinois.

- CITL. (2024, November). “Clear goals, multiple means”. University of Illinois.

Quick Win 3: Build a Supportive and Inclusive Learning Community

Creating a supportive and inclusive community is a key principle of UDL’s focus on fostering engagement through social interaction.3 When students feel a sense of belonging and connection, they are more likely to stay motivated and persist in their learning. UDL encourages collaborative activities, peer feedback opportunities, and low-stakes discussion prompts to help students interact with each other and the content. Building an inclusive learning environment where diverse perspectives are valued can help combat disengagement and foster a positive, motivating atmosphere.

- STEM Example: In a computer science course, have students collaborate on debugging each other’s code in small teams, turning problem-solving into a social, interactive activity.

- Arts Example: In a music appreciation course, encourage students to share a song from their cultural background and discuss how it relates to musical concepts learned in class.

- Health Sciences Example: In a nursing course, create peer mentorship groups where students can support each other in studying medical terminology and patient case studies.

- Business Example: In a marketing course, organize small groups to work on analyzing different company ad campaigns, fostering collaborative problem-solving.

- Sociology Example: In a sociology class, have students collaborate on a community service project where they can apply sociological theories to real-world problems, creating a deeper connection to the material.

Quick Win 4: Provide Frequent and Supportive Feedback

Frequent and constructive feedback is an essential part of the UDL principle of providing multiple means of representation. By offering timely, actionable, and growth-oriented feedback, educators help students see their progress and understand how to improve.4 UDL emphasizes positive reinforcement and "wise feedback," combining encouragement with constructive criticism to help students remain motivated and persistent. Timely feedback, whether through automated responses or tools in the LMS, peer review, or quick video responses, can help reinforce student engagement by making students feel supported and capable.

- Math Example: Instead of just marking incorrect answers on a calculus exam, use digital tools like Desmos or Wolfram Alpha to show students step-by-step corrections and explanations.

- English Example: In a writing course, offer audio or video feedback on student drafts, pointing out strengths and providing targeted revision suggestions to make feedback feel more personal.

- Engineering Example: In a project-based engineering class, provide students with structured feedback loops where they receive formative feedback at different design stages, preventing last-minute frustration.

- Theater Example: In a drama course, provide video feedback on student performances, highlighting strengths and giving actionable tips for improvement.

- Psychology Example: In a developmental psychology course, offer feedback on quizzes or assignments that include suggestions for further reading or practical applications of the theories discussed.

For more on Providing Frequent and Supportive Feedback, see the following CITL UDL Tip of the Month articles:

- CITL. (2025, February). Wise feedback and UDL strategies for promoting learner agency. University of Illinois.

- CITL. (2024, March). Fostering expert learners. University of Illinois.

Quick Win 5: Reduce Barriers That Lead to Frustration

Reducing barriers to learning is at the heart of UDL’s goal to create flexible learning environments that accommodate diverse needs and reduce unnecessary challenges. When students encounter barriers—whether they are in the form of unclear instructions, inaccessible content, or rigid deadlines—it can lead to frustration and disengagement.5 UDL encourages instructors to provide scaffolding, such as breaking large projects into manageable tasks, offering flexible deadlines, or providing supplementary resources to ensure students can succeed.

- STEM Example: In a chemistry lab course, provide students with pre-lab instructional videos so they can review complex procedures before arriving in class, reducing confusion during experiments.

- Business Example: In a finance course, break a semester-long stock market analysis project into smaller milestones with check-ins to prevent students from feeling overwhelmed.

- Education Example: In an online course for future educators, use scaffolded discussion boards where students first reflect individually, then discuss in small groups before posting final responses.

- Psychology Example: In a psychology course, provide students with summary notes and concept maps after each lecture to help them consolidate their learning and reduce cognitive overload.

- Art Example: In an art course, offer students various tools for creating digital art, such as tutorials on software basics, to reduce the frustration of learning new technology while maintaining focus on the artistic process.

For more on Reducing Barriers, see the following CITL UDL Tip of the Month articles:

- CITL. (2024, February). Three strategies for removing barriers and threats. University of Illinois.

- CITL. (2024, February). Building Bridges: UDL and Instructional Scaffolding. University of Illinois.

Conclusion

Overall, disengagement doesn’t necessarily mean students lack interest. It often reflects students’ struggles with motivation, confidence, or a sense of connection. By applying UDL principles—offering relevance and choice, providing feedback and community, and reducing barriers—you can create a learning environment that keeps students motivated and supports a persistent, ongoing learning experience.

References

- CAST. (2018). Provide options for recruiting interest: Relevance, value, and authenticity. Universal Design for Learning Guidelines. Retrieved from https://udlguidelines.cast.org/engagement/interests-identities/relevance-value-authenticity/

- CAST. (2018). Provide multiple means of action and expression. Universal Design for Learning Guidelines. Retrieved from https://udlguidelines.cast.org/action-expression/

- CAST. (2018). Foster collaboration and community. Universal Design for Learning Guidelines. Retrieved from https://udlguidelines.cast.org/engagement/effort-persistence/belonging-community/

- CAST. (2018). Provide mastery-oriented feedback. Universal Design for Learning Guidelines. Retrieved from https://udlguidelines.cast.org/engagement/effort-persistence/feedback/

- Vanderbilt University. (2024). Universal design for learning (UDL): What do we mean by UDL? IRIS Center. Retrieved from https://iris.peabody.vanderbilt.edu/module/udl/cresource/q1/p03x/#content

Common Myths and Misconceptions about UDL

By Marc Thompson (CITL)

Universal Design for Learning (UDL) continues to gain traction as a powerful framework for designing inclusive and effective learning experiences. However, despite its growing adoption, several myths and misconceptions persist, often leading to misunderstandings about the purpose and implementation of UDL. This month let’s take a few minutes to debunk a few of the most common misconceptions and clarify what UDL truly is and isn’t.

Myth #1: UDL is Just for Students with Disabilities

One of the most prevalent myths about UDL is that it’s solely about accommodating students with disabilities. While accessibility is a key component, UDL is broader in its scope because it is designed to benefit all learners by providing multiple ways to engage, represent information, and express understanding. For example, offering video captions doesn’t just support students who are Deaf or Hard of Hearing—it also benefits English language learners and students who prefer to read along while listening. As discussed in our September 2024 Tip of the Month Article, Embracing Learner Variability, UDL fosters inclusive learning environments that are flexible and adaptable and that recognize the variability of all learners, not just those with disabilities. That said, it is important to remember that while UDL strategies often reduce barriers to learning, they do not replace the need for specific accommodations, assistive technologies, and related supports that remain essential for ensuring students receive equal opportunities that meet their individual learning needs.

Myth #2: UDL Means Lowering Academic Standards

Some also worry that implementing UDL will dilute academic rigor or oversimplify coursework. In truth, UDL is about removing unnecessary barriers, not reducing expectations. For instance, allowing students to demonstrate their understanding through different formats—such as a written paper, recorded presentation, or infographic—doesn’t necessarily change the learning outcomes; it simply gives students greater flexibility in how they achieve them. UDL does this by providing multiple means for students to access challenging content and demonstrate mastery in ways that align with their strengths. For more information, see our February 2024 UDL Tip of the Month article, 3 Strategies for Removing Barriers.

Myth #3: UDL Requires Completely Redesigning Your Course

Another common misconception is that adopting UDL means overhauling your entire course from scratch. While proactive course design is ideal, UDL can be implemented gradually through small, intentional changes. In Reach Everyone, Teach Everyone, Thomas Tobin refers to this iterative process as the +1 Method. For example, starting by adding alternative text to images, or by providing a choice between discussion formats (written or recorded), or by using structured headings in documents—these are all incremental changes that can be made over time. Taking time to evaluate the impact of the changes you make is equally important and allows for ongoing fine-tuning. In keeping with the University of Illinois Campus-wide Definition of Teaching Excellence, this iterative process underscores the importance of course design that is “reflective and evolving.” Overall, incremental, accretive adjustments can have a significant impact on student engagement and comprehension without requiring a wholesale course redesign.

Myth #4: UDL is Only About Technology

While technology can certainly support UDL implementation, it is not a requirement. UDL is about flexible, inclusive instructional approaches that can be applied in any learning environment. For example, a history professor might use storytelling, group discussions, and primary source documents to engage students in different ways, ensuring multiple entry points into the content and relevant learning outcomes. Whether high-tech or low-tech, UDL is about providing meaningful choices and relevant scaffolding to support diverse learners. For more on the importance and implementation of scaffolding, see our December 2024 UDL Tip of the Month article, Building Bridges: UDL and Instructional Scaffolding.

Ultimately, dispelling some of the common myths and misconceptions about UDL should be helpful in better understanding how UDL can enhance learning for all students. UDL isn’t about special treatment or extra work—it’s about thoughtful, intentional course design that reduces barriers, increases engagement, and helps foster “expert learners.” For more on UDL and expert learners, see our March 2024 UDL Tip of the Month article on Fostering Expert Learners. In the end, and over time, those small +1 changes add up and can lead to big improvements in student success by making learning more equitable, engaging, and effective.

Wise Feedback and UDL Strategies for Promoting Learner Agency

Most of us would agree that feedback can be a powerful teaching tool. When done thoughtfully, it’s much more than correcting mistakes—it’s about empowering students to see their potential and to promote a growth mindset. That’s where “wise feedback” comes in. Closely aligned with the Universal Design for Learning (UDL) goal of creating learner agency, wise feedback encourages students by setting high expectations, offering actionable steps, and showing that you believe in their ability to succeed (CAST, 2024). It’s the kind of action-oriented feedback that helps students become what the UDL framework describes as “expert learners”—those who are purposeful, resourceful, and motivated (Thompson, 2024).

So, what does wise feedback look like in action?

Imagine you’re teaching a biology class, and a student submits a lab report on mitosis. Instead of just pointing out errors, you might say, “You’ve done a great job outlining the stages of mitosis! To take this further, let’s connect each stage to a real-world example—for instance, how errors in cell division might cause medical issues. I know you can add this extra layer of analysis!” This kind of feedback celebrates the student’s effort while gently pushing them to think more critically. Or, in a creative writing course, you could say, “Your story has a compelling plot! I’d love to see your protagonist’s emotions explored and developed a bit more. Why not try adding a scene where they face a personal challenge—it may make their journey even more relatable.”

Creating a Supporting Environment

Wise feedback also helps create a classroom environment where students feel supported and capable (Bose, 2020). It’s not just about what you say but how you say it. Phrasing like, “I’m giving you these suggestions because I know you’re capable of achieving great results,” can make a big difference. It shows you’re invested in the student’s growth. If you’re teaching a business class, for example, and critiquing a student’s marketing proposal, you might frame it like this: “This is a strong start! I know you’re capable of developing an even more targeted strategy. Let’s think about how to refine your audience profile to make it sharper.” Coupled with tools like rubrics or samples of exemplary work, this kind of feedback feels more actionable and less overwhelming (CAST, 2024).

Learner Agency

Finally, wise feedback encourages students to take the reins and reflect on their learning. In an art history course, for instance, you could ask students to review peer feedback on their visual analysis and create a short plan for improvement. Or in a math class, you could guide students to use a self-assessment checklist to track their progress based on your comments. The checklist might include questions like "Did I show my work clearly?" and "Did I communicate the reasoning behind each step of the solution path?” Students could then use your comments to identify areas where they can improve, such as explaining their reasoning more thoroughly or practicing a specific type of problem. These small actions build confidence and self-regulation, and help provide a strong foundation for future learning that will help students develop the skills they’ll need far beyond your course.